Production Reference:

Production Reference:|

|

Translator's Note: Super Robot Generation: Sunrise 1977-1987, volume 34 of Newtype 100% Collection series, is an in-depth retrospective of the robot anime produced in the ten years between the establishment of Nippon Sunrise and the studio's eventual renaming as "Sunrise, Inc." In addition to Mobile Suit Gundam and the sequel series Z Gundam and Gundam ZZ, these include many other landmark works by Gundam director Yoshiyuki Tomino. Published in March 1999, just before the debut of ∀ Gundam, this book includes in-depth interviews with Tomino and some other notable creators, as well as shorter staff comments on specific works and lots of analysis and behind-the-scenes production info. I'll continue adding to this page as I make my way through the book's contents. |

Before a work begins airing, it goes through many twists and turns and situations the ordinary viewer never knows about. Here, as we look back on the history of the robot anime from the Nippon Sunrise era from a comprehensive perspective, we'll also introduce these valuable behind-the-scenes stories and the roots of the works themselves, based on in-depth reporting.

Sunrise's predecessor, Sunrise Studio (Ltd.), was established in September 1972. The works created in this era included Zero Tester (produced with Soeisha), Brave Raideen (produced with Tohoku Shinsha), and Super Electromagnetic Robo Com-Battler V (produced with Toei). (1)

Around this time, Sunrise made contact with Clover, a toymaker that was looking to grow its business by sponsoring a TV anime program. This goal was aligned with that of Sunrise, which had always wanted to launch an original work. In November 1976, the company changed its name to Nippon Sunrise (Inc.) and began working on an original plan. This became Super Machine Zambot 3, which began airing in October 1977.

Zambot was well-received in terms of both audience ratings and toy sales, and after a three-month blank following the end of the series, The Unchallengeable Daitarn 3 began airing in June 1978. Because the audience might get bored with the serious approach of the previous work, Daitarn switched to a comedy approach and earned a favorable reception.

With the success of these two works, and the tailwind of the anime boom which was then reaching its peak, Sunrise began planning "a taiga drama-style anime aimed at late teens." This plan became Mobile Suit Gundam, which began airing in April 1979 and turned into a hit series that still continues to this day.

1977 Super Machine Zambot 3

• A giant battery-operated toy standing 44 cm tall. With the hit success of Zambot and Daitarn, Clover became a major toymaker overnight.

1979 Mobile Suit Gundam

• At the start of planning, the concept was that the Zaku would be the only type of enemy robot, as represented by this shot from the opening.

• A comic published by Akita Shoten (by Yu Okazaki). This is a collection of the story serialized in "Adventure King" during the broadcast. Yu Okazaki also did a Daitarn 3 serial in the same magazine.

• "How to Build Gundam," published by Hobby Japan. As a groundbreaking mook devoted only to Gunpla customization techniques and dioramas, this drew much attention at the time.

Though Gundam became a major hit, its toy sales were sluggish during its broadcast run, so it was decided that the next work would be created "purely for children." This was The Unchallengeable Trider G7, which began airing in February 1980. The protagonist's image would be that of a lively and mischievous boy, which was rare in the anime of the time. From there, the work went in the direction of a "working-class humanity story." (2)

Meanwhile, Sunrise received a request from the toymaker Tomy, which had sponsored the 1979 Sunrise-produced anime Science Adventure Command Tansar 5. Tomy wanted to create a robot anime which made use of the one-touch transformation feature that was so popular in Tansar 5, while adding a robot combination. Thus the planning of Space Runaway Ideon began. Ideon began airing in May 1980, and though its toy sales were disappointing, it evolved into a masterpiece whose content ventured into the realm of philosophy, and which had a great influence on the later anime scene.

Since the previous Trider G7 had been successful in terms of both toy sales and audience ratings, it was decided that the followup work would also target a younger audience. Robot King Daioja, which began airing in January 1981, was an orthodox robot anime in which good was rewarded and evil punished, incorporating the flavor of Mito Kōmon. (3)

1980 The Unchallengeable Trider G7

• An encyclopedia published by Kodansha. In addition to a cover illustration by Kunio Okawara, it was packed with mecha, character, and story information, as well as original illustrations by Yutaka Izubuchi.

1980 Space Runaway Ideon

• A deluxe toy released by Tomy. Though its combining gimmick was superb, the impression it gave was very far from the image of the TV version.

• "Space Runaway Ideon & The World of Yoshiyuki Tomino," a mook published by Kodansha. Before this, there had never been a mook named after an anime director.

• The Ideon using the wave motion gun introduced in the middle of the program. This weapon, which generated mini black holes, was the most powerful in anime history.

Fang of the Sun Dougram began airing in October 1981. It was launched because Gundam and Ideon had demonstrated that robot anime could also be targeted at late teens. Since the work's narrative was realistic, so was the mecha, and gimmicks such as transformation and combination were eliminated from the main robot.

In February 1982, Blue Gale Xabungle began as a followup program to Daioja. Because toys of the three combining robots from Daioja hadn't sold well, this plan returned to the approach of "each mecha transforms and then they combine into a robot." However, because the robot itself had been designed ahead of time, there was too large a gap between it and the worldview of the work itself. Thus the Walker Galliar, the first replacement robot in anime history, was introduced in mid-story. With this program, the toymaker Bandai also began releasing plastic models in a form that didn't conflict with Clover's toys.

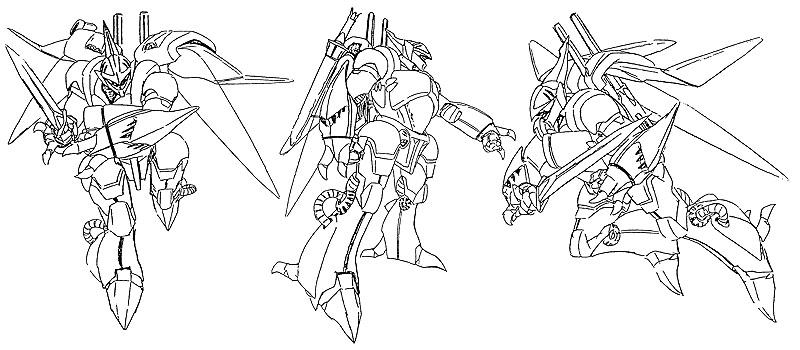

The following year, in February 1983, Aura Battler Dunbine started in the same time slot. This incorporated elements of heroic fantasy, and its insect-themed robots also gained popularity. In August of that year, the main sponsor Clover went bankrupt. The production thus had to deal with an unprecedented situation, and the broadcast run ended with 49 episodes instead of the planned 50.

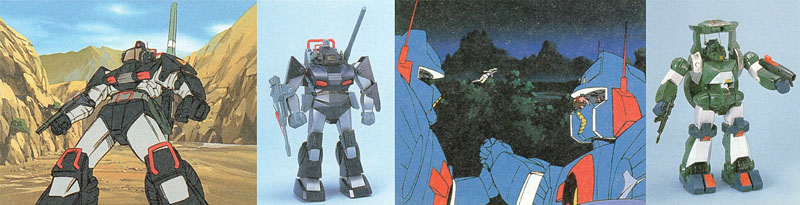

1981 Fang of the Sun Dougram

• The Dougram was the first faceless robot in anime history. Though the realistic mecha setting was a selling point, the dramatization often depicted it like a hero robot.

• The Dual Models, hybrid toys made from plastic and die-cast metal, were a big hit. The internal mechanisms were also reproduced in precise detail.

1982 Blue Gale Xabungle

• Viewers were surprised when other robots of the same type as the main robot Xabungle appeared from the very first episode.

• A deluxe toy of the replacement robot, the Walker Galliar, released by Clover. All its joints were movable, and it separated and transformed just as in the setting.

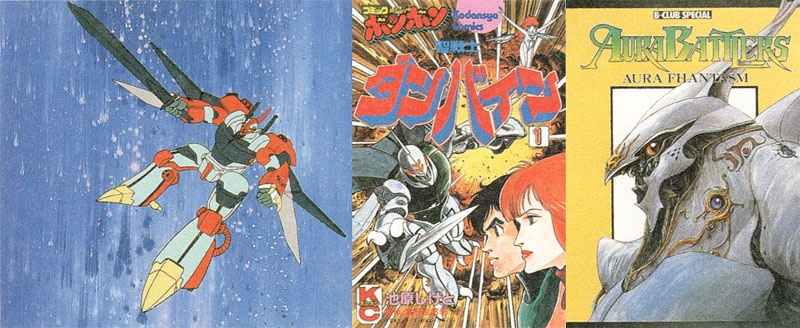

1983 Aura Battler Dunbine

• The Billbine was introduced in the second half of the program. Its name was a combination of "Dunbine" and "Build," as in "make a new robot."

• A comic version published by Kodansha (by Shigeto Ikehara). Though it was serialized in a children's magazine at the time of broadcast, it had hard content that depicted the TV story relatively faithfully.

• A mook published by Bandai. Focused exclusively on the aura battlers, it included valuable material such as early setting and original aura battlers.

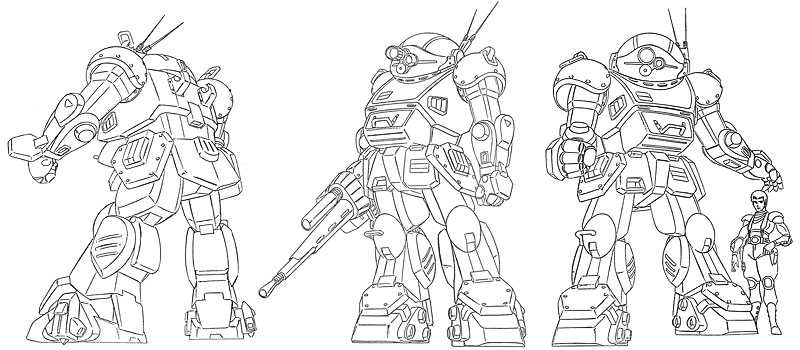

Armored Trooper Votoms began airing in April 1983, around the same time as Dunbine, as a followup program to the long-running Dougram. The military aspects were emphasized even more than in Dougram, and the realistic design thoroughly eliminated all heroic elements from the main robot. At the same time, the core narrative itself had a strong fantasy element in the form of Wiseman, an entity that transcended humanity. This was also Sunrise's first attempt to use a title that didn't include the name of the main robot.

The broadcast of Round Vernian Vifam began in October 1983. With a typical anime, the plan would be launched a year before it aired, but with Vifam this was an unusually short period of 8 months. It's also noteworthy that this work revived the original plan for Gundam, which was a space version of Two Years' Vacation. From this point on, the focus of the merchandising changed from traditional die-cast toys to plastic models and realistic toys made from shock-resistant ABS resin.

Heavy Metal L-Gaim began airing in January 1984 as a successor to Dunbine. Responding to the demands of fans who had begun to emphasize the mecha setting, the robot designs incorporated new and unprecedented ideas such as the use of rubber in their fingers.

1983 Armored Trooper Votoms

• The military aspects, such as the fact that various optional weapons could be attached to the basic Scopedog, also increased its popularity.

• A picture book published by Kodansha, with content designed for younger readers. It's interesting that, in contrast to the hard content, it kept to the picture book format and included catchphrases such as "Let's all sing it together" in reference to the theme song.

• Toys released as part of the second round of Dual Models after Dougram. The landing pose, arm punch, and other gimmicks were reproduced quite faithfully.

1983 Round Vernian Vifam

• As a main mecha, the robot had few heroic traits. But as the story itself grew in popularity, sales of the plastic models increased as well.

1984 Heavy Metal L-Gaim

• A deluxe toy released by Bandai. It attracted attention with mobility and balance not seen in traditional alloys, which enabled it to stand on one leg.

Yoshikazu Yasuhiko, who had become an overnight celebrity with his character designs for Gundam, brought a plan to Sunrise which began airing in April 1984 as Giant Gorg. While the robot animation of the time focused on realistic approaches, this one developed into a straightforward adventure story aimed at young boys, and it was a high-quality work in which Yasuhiko applied his personal touch to the animation as well.

Panzer World Galient started in October 1984. The world of the story, which incorporated a Western flavor not seen in previous Sunrise works, anticipated the "sword and sorcery" boom centered on video games that began in 1986. Perhaps it was a masterpiece that came ahead of its time. Like Votoms, it was sponsored by Takara, but because the Votoms toy merchandising had fared poorly, the main robot in this work included gimmicks like transformation and combination.

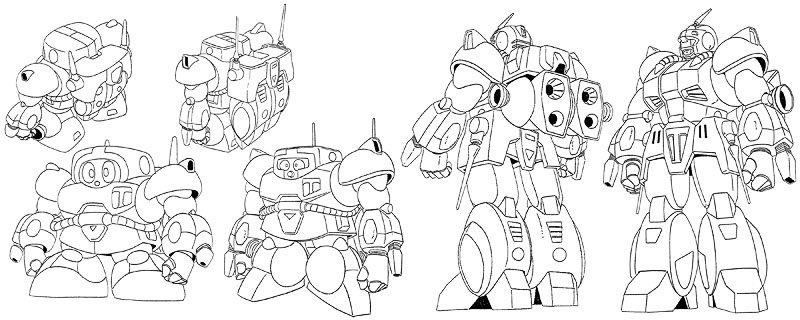

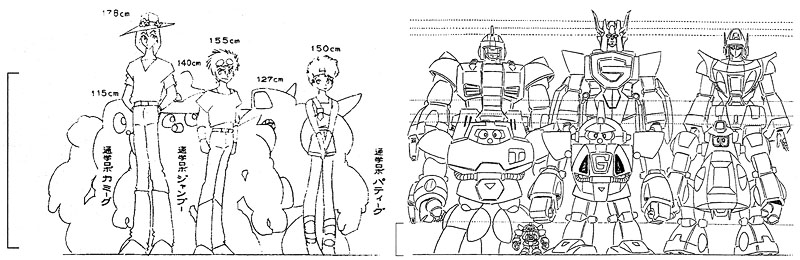

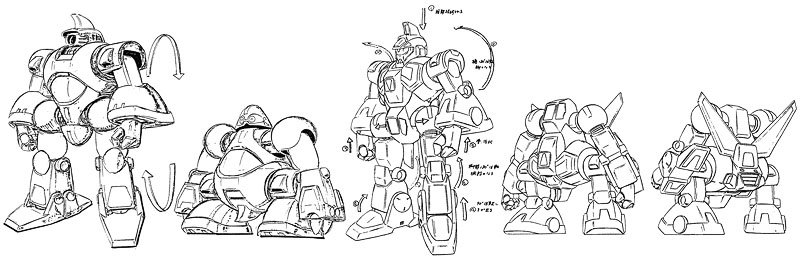

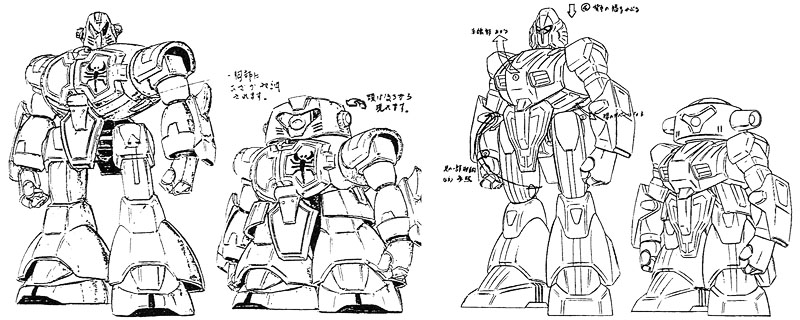

Super Robot Galatt, Sunrise's first gag robot show, began airing in the Tokyo region on the same day as Galient. The selling point was that the main robots changed from two-head-tall deformed types, which were starting to become popular at the time, into hero types. This was also the work that introduced the "morphing" element to the robot genre. (4)

1984 Giant Gorg

• The touch of the original creator Yoshikazu Yashiko was foregrounded not only in the work's story, but in the onscreen layout and animation as well.

1984 Panzer World Galient

• The unique world setting had a medieval European motif. The robots that appeared were excavated from beneath the ruins of an ancient civilization.

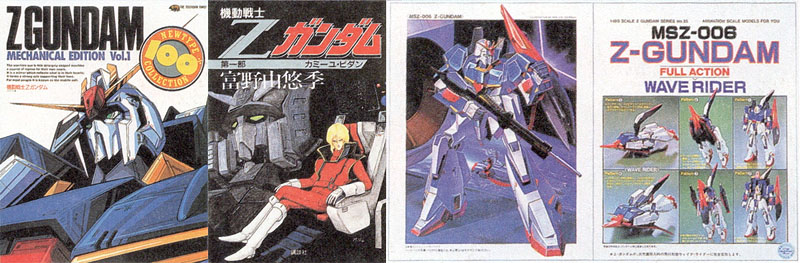

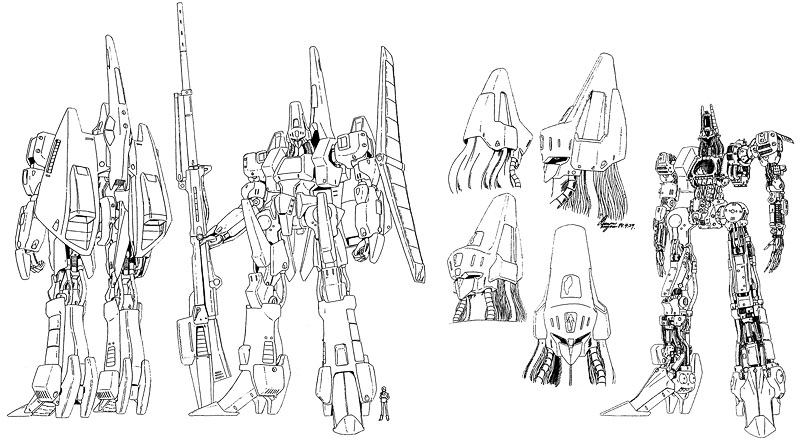

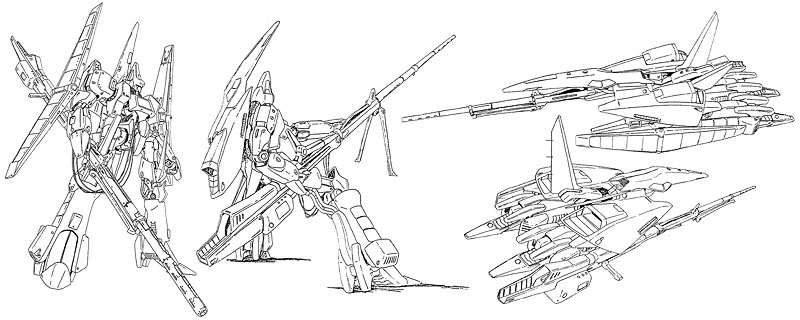

Mobile Suit Z Gundam, the sequel to Mobile Suit Gundam, began airing in March 1985. The plan was proposed from the Bandai side because, in short, Bandai had run out of material for the mobile suits it was releasing as plastic models.

The setting within the program for the main mecha, the Gundam Mk-II, was that it was a successor to the first Gundam. But in design terms, it was based on the concept of what the first Gundam, which retained many elements of hero robots, would be like if it were refined in 1985. The true main mecha, the Zeta Gundam, was meant from the beginning to appear in the latter half of the program. This was partly because it was a mobile suit with a new concept whose design and product development required more time.

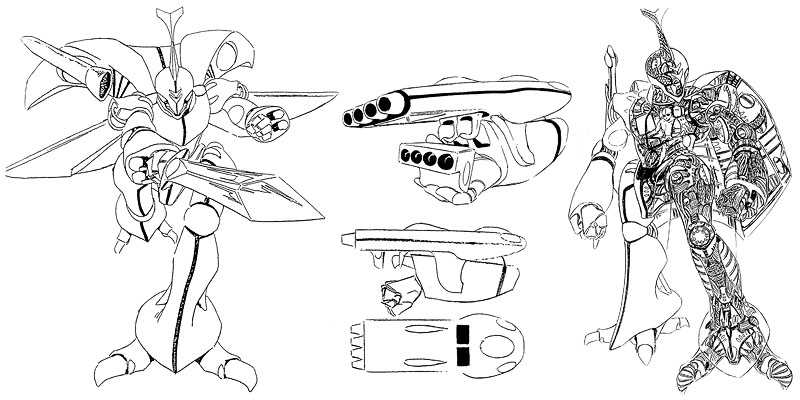

Next, Blue Comet SPT Layzner started in October 1985. Reflecting an era which preferred rectilinear mecha, the main mecha had sharp design lines. The innovative head was inspired by the cockpits of fighter aircraft, making this a design partway between hero robots and real robots.

Around this time, Sunrise also began entering the field of video media in earnest, with continuations of works such as Votoms and Vifam that had been popular on television.

1985 Mobile Suit Z Gundam

• A mook published by Kadokawa Shoten. In addition to the mechanical edition shown here, there was also a character edition. These were all republished in 1998, and are still available.

• A novel version published by Kodansha. This was a novelization by Director Tomino, with cover illustrations by Mamoru Nagano. Depicting Char and the mobile suits with an approach different from the TV version, these were very appealing.

• A plastic model released by Bandai. The transformation gimmick was featured on the packaging, making a selling point of the fact that this was the first transforming mobile suit and that the product also transformed perfectly.

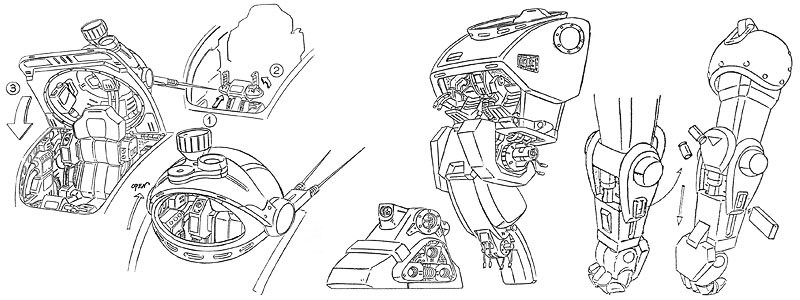

In March 1986, Mobile Suit Gundam ZZ began airing as a followup program to the well-received Z Gundam. The ZZ Gundam was given a heavyweight design to contrast with the sharp impression of the Zeta Gundam. In order to explain the Gundam world to younger fans, a special program called "Prelude ZZ" was broadcast as the first episode. This was also done to buy time for production, since the decision to air ZZ had been made so late.

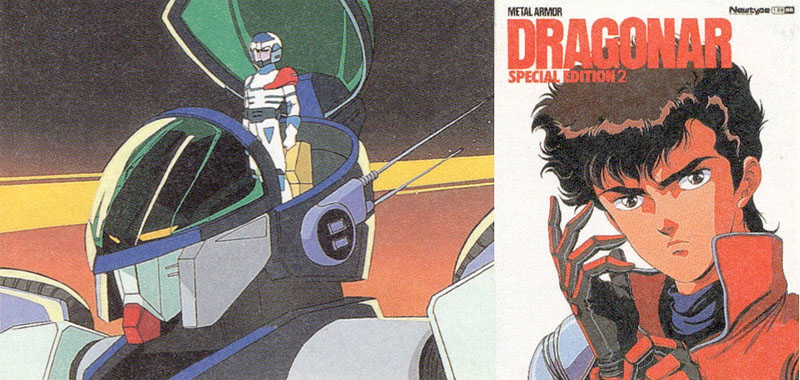

After this, Metal Armor Dragonar started in February 1987. Its simple forms, inspired by the first Gundam, were an antithesis to the mecha designs of robot anime which had become overly complicated.

In April 1987, during the broadcast of Dragonar, the company name was changed to Sunrise (Inc.). In the 1990s, it went on to create new robot shows such as the "Brave" and "Eldran" series.

1985 Blue Comet SPT Layzner

• The "Layzner" title evoked the image of optical weapons such as lasers and rayguns, and the logo design was also very sharp.

1987 Metal Armor Dragonar

• A mook published by Kadokawa Shoten. It included detailed specs for the metal armors and other mecha, as well as story and character information.

(1) Following 1976's Com-Battler V, Sunrise went on to produce several other robot anime series for Toei—1977's Voltes V, 1978's Daimos, and 1979's Daltanious. Mecha designer Yutaka Izubuchi, who created enemy robots for Daimos and Daltanious, went on to play the same role on Sunrise's own Trider G7 and Daioja.

(2) The Japanese phrase 下町人情 (shitamachi ninjō), literally something like "downtown human sentiments," apparently means "the compassionate feelings of middle- and lower-class people."

(3) Mito Kōmon was a long-running period drama in which a wandering hero dispenses justice. "Daijoa" was essentially a science fiction version of this premise.

(4) The term used here, 変身 (henshin), means "metamorphosis" or "shapeshifting." It's commonly used in connection to superheroes and live-action special effects shows such as Kamen Rider and the Super Sentai (Power Rangers) series.

Translator's Note: Although this section of the book is filled with mecha setting art and commentary, I've focused here on translating the parts that provide critical analysis or behind-the-scenes production info, rather than simply describing the mecha and the onscreen story.

Story • The Gaizok have come from outer space to destroy the Earth. In this time of crisis, the Jin family, the descendants of aliens who once fled to Earth when their homeland was destroyed by the Gaizok, rise up with the spaceship King Bial and the giant robot Zambot 3. But as the people caught up in the conflict turn their anger against the Jin family rather than the Gaizok, the Jin family are forced to fight a lonely battle...

Commentary • As the studio's first original work, it focused on aspects that traditional robot anime had overlooked. Politicians and people fleeing during battles with the enemy were depicted onscreen in a naturalistic way. Through its portrayal of the Jin family, this unique work also questioned the bonds between family members, their respective roles, and the nature of justice. It aired at 5:30 PM Saturdays on the Nagoya Broadcasting Network, and ran from October 8, 1977, to March 25, 1978. 23 episodes total.

Staff •

Cast •

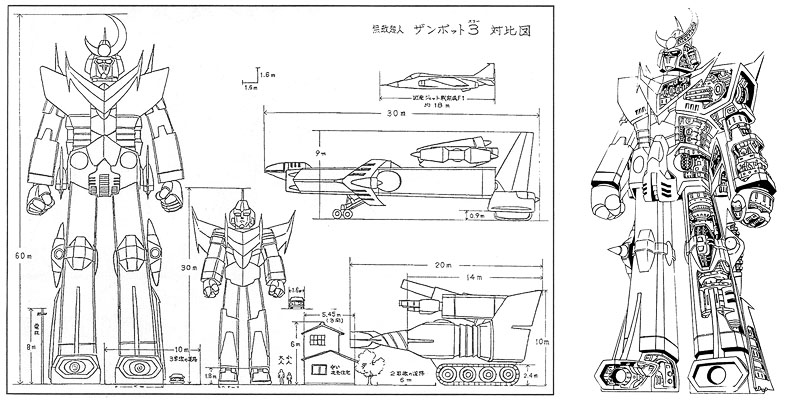

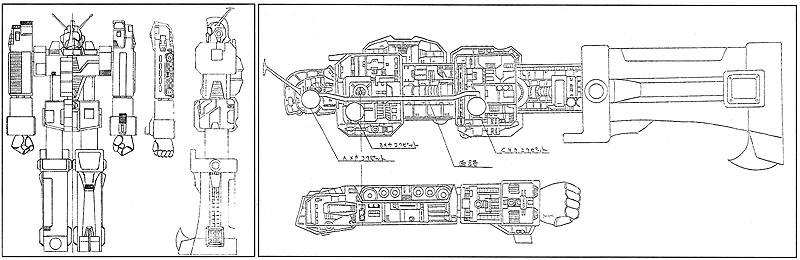

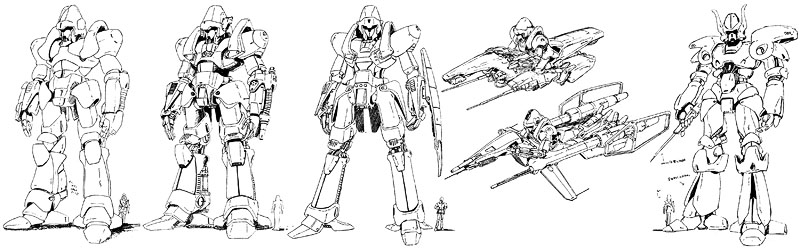

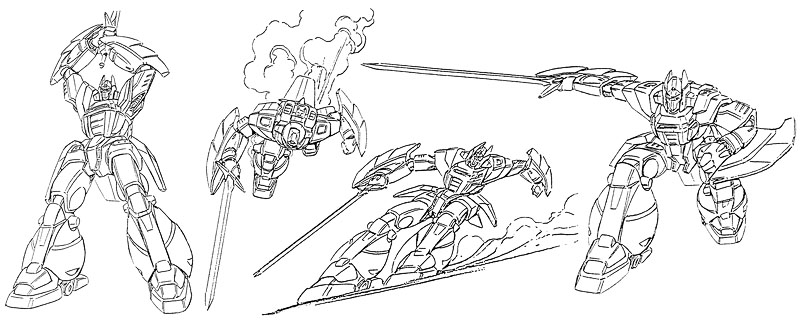

Zambot 3: A version cleaned up by Yoshikazu Yasuhiko. The design has a fairly large number of lines for a robot of its time. It's distinguished by an overall design based Japanese armor and samurai, with a crescent moon-shaped decoration on its head and protruding shoulders. Its armament is also unified by this concept.

Internal cutaway: Sunrise's materials say this was drawn by Studio Nue, and in his interview at the end of this book Okawara himself says he didn't touch it this design, but it's also been said that this was created by Kunio Okawara and the details are unclear.

Comparison diagram: The main mecha and fighter aircraft compared to people and buildings. We can see how huge all the Zambot mecha are.

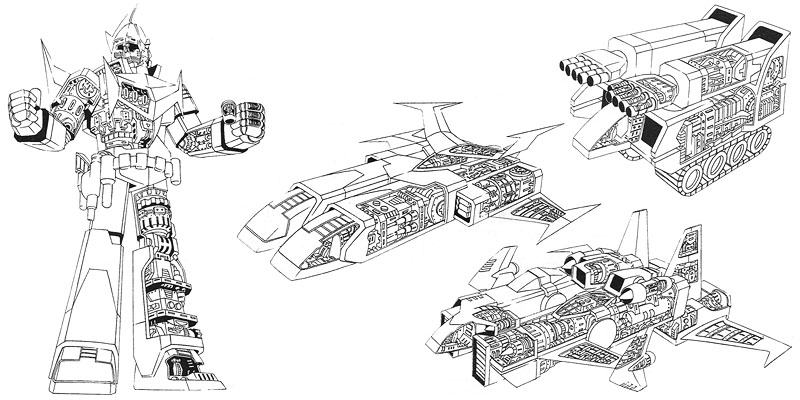

Zambot mecha internal cutaways: This internal cutaway setting for each of the Zambot mecha was apparently drawn for magazine publication. The internal cutaways for the Zambo-Ace and Zambird, which are the same machine, were drawn with a consistent internal structure and take the storage gimmicks of the limbs into account. Likewise, the interiors of the Zambull and Zambase were carefully drawn so as not to contradict the internal cutaway of the Zambot 3.

In Zambot's planning meeting stage, a five-part combination was also proposed for the main robot, but planning proceeded with a three-part combination due to issues such as the sponsor's funds and technical capabilities, and to save labor in terms of setting and animation.

Yoshikazu Yasuhiko, who was responsible for character design, was very busy at the time. Thus he did only the characters and revisions to the main mecha, and wasn't directly involved with the animation of the actual show.

The broadcast itself ended after half a year, just as originally planned. But the audience ratings and toy sales were both favorable, so episode 22, "Eve of the Decisive Battle," was hastily produced as an extra insert episode. The animation was done by the staff of the followup program The Unchallengeable Daitarn 3.

As for the music, this was the first time Takeo Watanabe, who had previously worked on sports anime like Star of the Giants, World Masterpiece Theater anime, dramas, jidaigeki, and so forth, had ever been responsible for a robot anime. (1) His compositions filled with lyricism gave the story even greater depth.

The title "Zambot 3" combined the ideas of "three mecha that form a robot" and "Sunrise's robot."

At the time of Zambot 3, Sunrise had only just become a joint-stock company, and it was difficult because we had such a small staff.

I was the one who gave it the title "Super Machine Zambot 3." I chose "Super Machine" with the feeling that the protagonist's Jin family, as extraterrestrials, were supermen rather than ordinary humans. (2) Titles like "Invincible Robot" and "Mightiest Robot" were also suggested, but I figured we'd use those later on when we ran out of name ideas. (laughs)

We'd asked Mr. Ryoji Fujiwara to design the robot, but we also asked Mr. Yoshikazu Yasuhiko to clean it up so it would look cool when it moved in the animation. Mr. Yasuhiko had worked with Sunrise on things like Brave Raideen, so he already had a reputation for skillfulness.

The protagonist Kappei was established as being in the first year of middle school, but we made him shorter so that he'd be more relatable for an audience of children. Uchuta and Keiko have heights more appropriate for their ages.

On the cover of the proposal, the title of the work is written as "Zambot 3" without a subtitle, but inside the proposal it's written "Invincible Zambot." In this proposal, the mecha corresponding to the Zambo-Ace is tentatively named the "Sumo-Zambo," and the Zambase is the "Zamborg." The protagonist Kappei Jin is named "Amaoka Jin," and the other characters all share the same "Jin" family name.

The storyline described in the proposal is almost identical to the broadcast version, but there's also the idea of depicting discord within the Jin family as some of its members, afraid of battle, plan to escape from Earth.

Aside from this proposal, there's also another one by director Yoshiyuki Tomino. (3) In addition to a series structure plan for all 25 episodes, the character Shingo Kozuki is also mentioned here. (4) The main robot is tentatively named "Zambot Moon," and the enemy mecha are called "Mecha-Beetles" rather than Mecha-Boosts.

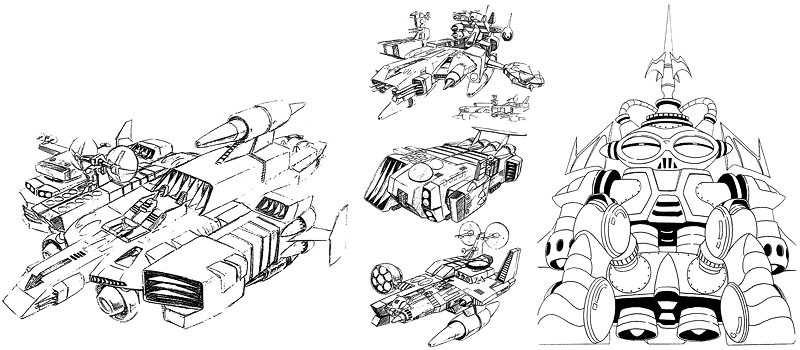

King Bial early design: This was drawn by Studio Nue, who were credited with design cooperation. The overall silhouette is identical to the final version, but the details and the transformation and combination gimmicks are very different.

Bandock early design: A rough draft of the enemy base Bandock, drawn by Kunio Okawara. Like the Zambot 3, it is designed to separate into three parts—head, torso, and legs.

Story • Banjo Haran rises up in the Daitarn 3 to crush the ambitions of the Meganoids, a gang of space cyborgs based on the planet Mars who plan to reconstruct and rule over all of humanity. Banjo calls for justice "for the world and for the people," but in fact his battle is also a form of revenge against his father, who developed the Meganoids and sacrificed the lives of his family...

Commentary • A work distinguished by its unique characters, such as a protagonist who began with the idea of "though he's a hero, he's not a hero inside or out," and who looks cheerful at first glance but would abandon his comrades in order to win; the Meganoid Koros, who believes humans can't live in peace without being controlled; and Garrison Tokida, who is aloof but regards battle very seriously. Amid the light dialogue with its comedic touch, we can catch glimpses of the passions and karma with which humans are burdened, adding depth to the story and creating a sense of mystery. It aired at 5:30 PM Saturdays on the Nagoya Broadcasting Network, starting June 3, 1978. 40 episodes total.

Staff •

Cast •

Daitarn 3: The decoration on the head is designed to resemble the helmets of Japanese armor. This was the third Sunrise-related giant robot with a mouth after Brave Raideen and Fighting General Daimos.

Internal cutaway: Internal cutaway diagrams by Kunio Okawara. It appears these were drawn for publication in magazines aimed at children. They were carefully drawn so that the internal structures are consistent in every form.

So as not to bore the audience, this work made a complete turnabout from its serious predecessor Zambot 3 and used a more comedic touch. Since the concept was a robot anime version of the British "007" movie series, the protagonist Banjo Haran was established as a young man, and two heroines who resembled Bond girls were included as well.

The rough character designs were drawn by Hitokazu Kokuni (a pen name for Tomonori Kogawa, later responsible for Space Runaway Ideon), and Kokuni also completed the enemy characters, while Banjo and his comrades were cleaned up for animation by Norio Shioyama. As for the mecha design, the main robot was a transforming type to differentiate it from the combining one in the previous work. The broadcast run was also extended to three cours.

This was the first time I was able to work with Sunrise in earnest. The planning of Daitarn 3 actually began before Zambot 3, but the sponsor went bankrupt, so it was temporarily put on hold. (7) It was later decided that Daitarn 3 would be the second Sunrise work.

The idea of one robot with a three-stage transformation was proposed by Mr. Eiji Yamaura, the head of the Sunrise planning department at the time. We quickly agreed that the tank form could provide power, and the aircraft form quick movement. In designing it, I remember being careful not to duplicate robots like Toei's Super Electromagnetic Machine Voltes V.

The title in the proposal is "Invincible Robo Daitarn 3," and though it's not clearly stated in the show itself, the chronological setting is established as 1988, about ten years after the broadcast. (5) In this proposal, the Mach Attacker is called the Protect Car, and when the Daitarn 3 transforms, it's called the Daitarn Fighter and Daitarn Tank. (6)

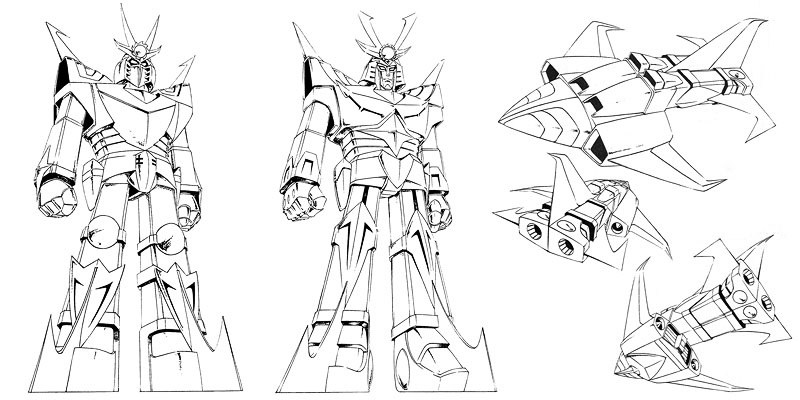

The names "Daitarn 3" and "Banjo Haran" were chosen by Director Tomino. Incidentally, Director Tomino is very fond of Banjo Haran, and he later published several novels about the character with a slightly altered setting. The mecha design was based on Japanese armor, which is particularly apparent in the heads of the two early designs on the left.

Story • In the year Universal Century 0079, the space colonies of the Principality of Zeon have declared their independence and begun an invasion of the Earth Federation. To oppose the Zeon forces, which have gained the upper hand in the war by deploying their new mobile suit weapons, the Federation Forces develop mobile suits of their own. A boy named Amuro Ray accidentally boards the prototype mobile suit Gundam, and together with the boys and girls fleeing the Zeon forces aboard the space carrier White Base, he is caught up in the maelstrom of war.

Commentary • It goes without saying that this is a monumental landmark of giant robot anime. Yoshiyuki Tomino, Yoshikazu Yasuhiko, Kunio Okawara, and other stellar talents came together to give birth to a realistic SF drama that defied all previous conventional wisdom. Its audience ratings failed to grow during its broadcast run, and it ended with episode 43, but it became a huge hit with the ardent support of anime fans and the success of the plastic models. Countless sequels and new works were created afterwards, and its popularity continues to this day. It aired from 5:30 to 6:00 PM Saturdays on the Nagoya Broadcasting Network. 43 episodes total. The broadcast ran from April 7, 1979, to January 26, 1980.

Staff • Planning /

Cast •

The "mobile suit," which positioned the giant robot as a futuristic weapon, was derived from the powered suits that appear in R.A. Heinlein's novel Starship Troopers. In the earliest proposal plan, "Space Combat Team Gunboy" (tentative title, Nagoya TV Programming Department), these were powered suits referred to as giant mobile infantry, but by the time of "Mobile Steel Man Gunvoy" (tentative title, Sotsu Agency) they had become "mobile suits," and the setting used in the broadcast version had more or less taken shape.

Thanks to detailed setting such as Minovsky particles that disrupt radio waves, and attitude control using the movement of mass in outer space, a world was painstakingly constructed in which "it's not unreasonable for giant robots to engage in visual-range combat." Fans were fascinated by the realism this created. Of course, we also shouldn't forget the appeal of the characters, who were filled with the same kind of realism.

The Gundam's design was initially something like a diving suit. The idea came from Starship Troopers, so even though it was a giant robot, it still had the image of a powered suit. Thus I wondered whether I could make a robot that wasn't just a combination of blocks and cylinders, like the previous Zambot and Daitarn, and I believe that's why I gave it calves. It also reflected the ideas of many other people, and finally Mr. (Yoshikazu) Yasuhiko put it all together according to his own taste. I think that's why it ended up having such a cool, great-looking silhouette that's still easy to draw.

The details of the Gundam's face may be troublesome, but it's pretty easy to get the shape. There hadn't really been a face like that before, though, so it may have been hard for the animators to draw. Even I had trouble with it. It's full of pitfalls. (laughs) It doesn't have a mouth because it's better not to have one in a robot show for grown-ups.

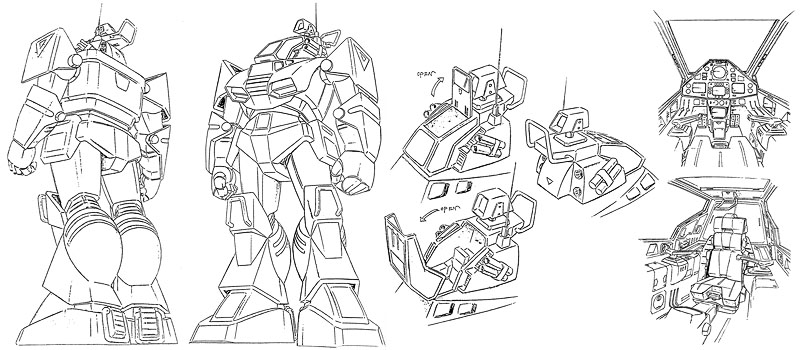

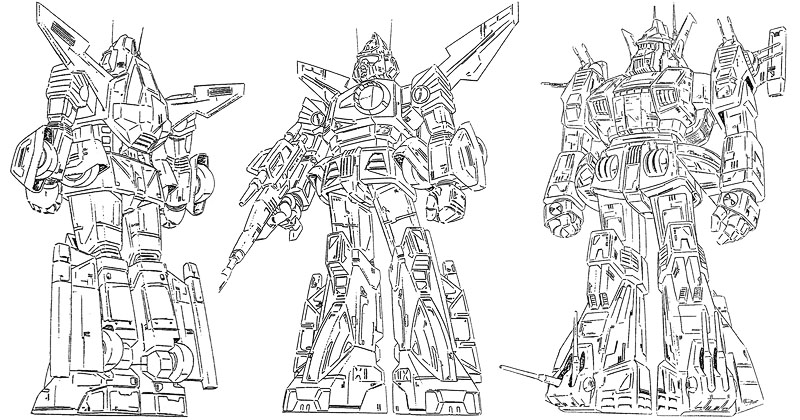

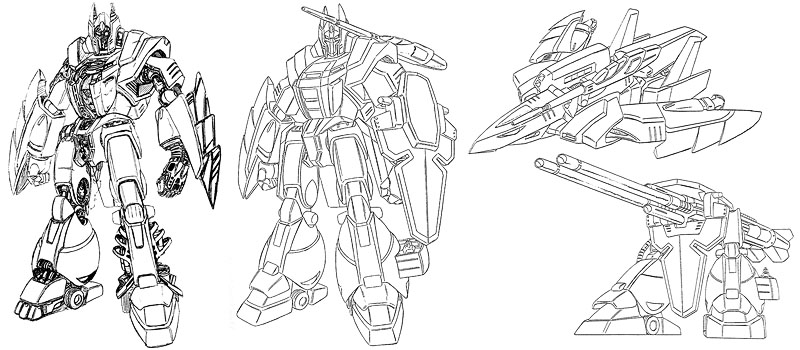

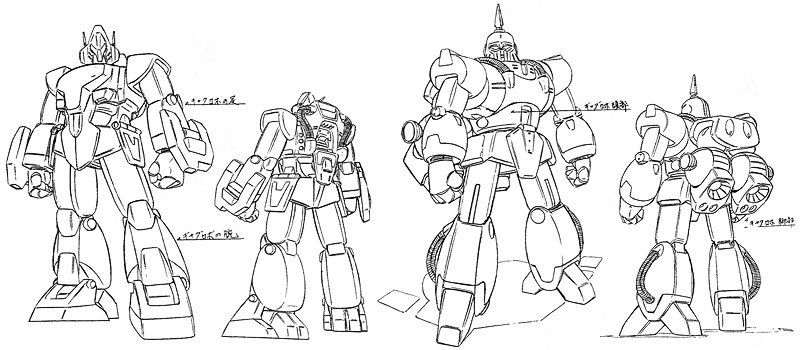

The Gundam's design began with a realistic approach unprecedented in anime robots, attempting to break away from previous robot designs. Here, we will introduce some of the unique designs produced along the way.

Gundam: A "Gundam with a mouth" was also designed, in the tradition of the Daitarn. In the image at left, it's carrying a spray gun. At center is fully equipped Gundam designed for the toy version. The equipment is completely original.

Guntank: A Guntank with hands instead of missile launchers. It also has machine guns in the turret section.

Core Fighter: A fairly crude Core Fighter compared to the final version. After being refined as per the image on the right, it was finally cleaned up by Yoshikazu Yasuhiko.

White Base: An early design for the space carrier White Base. This mecha was actually conceived during Daitarn 3, and it's inspired by the Sphinx.

Story • The Robot Empire, which plans to subjugate humanity, sends a succession of giant robots to attack Earth. Watta Takeo, a grade-school student who is also the president of an all-purpose space business called the Takeo General Company, battles this mysterious enemy using the giant robot Trider G7 that was left to him by his father.

Commentary • Incorporating elements of domestic situation comedy, this pioneered a new genre which could be called working-class robot anime. (8) It was an ambitious work that included some experimental elements, such as the fact that the story ends without the protagonist's side ever learning the enemy's true identity. The scenes of the robot launching from a public park also made a lasting impression. This was the first time Katsutoshi Sasaki, who had served as an assistant director under the late Tadao Nagahama, set out to direct a series, and it earned consistently high audience ratings. (9) It aired at 5:30 PM Saturdays on the Nagoya Broadcasting Network, starting February 2, 1980. 50 episodes total.

Staff •

Cast •

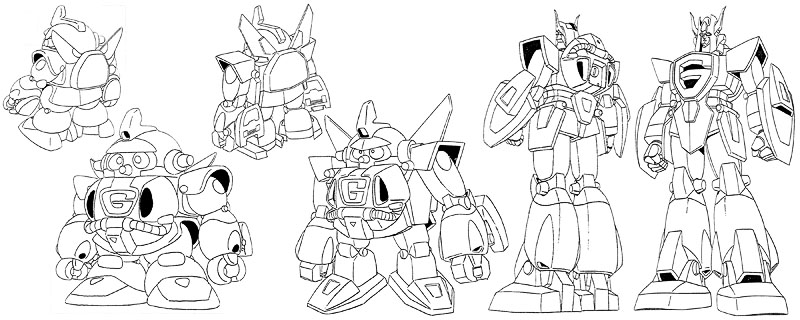

Trider G7: The Trider G7's hangar is underneath a public park. Part of its head protrudes into the park, and is normally part of a children's playground, but the park is designed to split in two during launch so that the Trider can take off. This unprecedented launch sequence, accompanied by the announcement "The Trider is now launching," also drew much attention.

The Tomino series airing on Nagoya TV, which had continued for three works starting with Zambot 3, came to a temporary end with Gundam, and The Unchallengeable Trider G7 was launched as a robot show aimed from the beginning at children. The reason for this change of direction was that the more serious Gundam had struggled both in terms of audience ratings and merchandising.

New mecha to power up the main robot appeared in the second half of the program, probably due to the popularity of Gundam's G-Armor. Such power-up mecha are taken for granted nowadays, but at the time, introducing new mecha tied so closely to the toys was still an unusual idea.

As for the design, the appointment of multiple character and mecha designers also succeeded in expanding the range of the visuals. In particular, the enemy mecha created by Yutaka Izubuchi, who was still a newcomer at the time, were beloved by fans who nicknamed them "Buchi-mecha."

This was another work for which I created a carved wooden mockup for presentation purposes. Since it had a transformation gimmick, I was also concerned about its strength when it was turned into a toy. Back then, unless you had something like that, sponsors often couldn't understand how it functioned.

Mr. Yutaka Izubuchi was in charge of the enemy robots, but I did pretty much everything on the main robot and its power-up parts. That was still an era where the standard was to have only one designer for a single work, so it was pretty tough. (laughs)

I'm sometimes asked whether the head design was meant to have a bird motif, but I went through a lot of trial and error as I tried to express the robot's heroic nature, and I only completed it after drawing many different variations.

In the early planning stages, I think the content was something like "A 22-year-old company president goes into space in his robot and fights gangs." We were thinking of something like Yujiro Ishihara's movies. (10) But we felt it would be better if the audience and the protagonist were closer in age, so we made him a grade-schooler.

At that time, actors who gave an impression of familiarity were starting to become more popular than handsome men and beautiful women, so rather than a superhero, we wanted the protagonist to be a straightforward boy who was bad at studying but had a kind heart. Thus we boldly decided on the setting of a grade-school student who was also a company president.

Once we'd come up with this image for the protagonist, we went in the direction of creating a working-class family drama. It was a work that got high audience ratings, and the toys sold well, too.

The Trider's transformations included the basic robot form, three forms of the head, and three forms of the main body, for a total of seven types. These seven transformations were an idea proposed by Sunrise. "Trider" was chosen as the name of the main robot, with the meaning "We'll try anything." But that didn't really work on its own, so they added "G7."

First the numeral "7" was appended because it transformed into seven types, and then the letter "G," which was not only the seventh letter of the alphabet but also had meanings like "great," "giant," and "ganbare." (11) This gave us the current title.

The protagonist's name "Watta Takeo" came, of course, from "a straightforward personality." (12)

Emblem Collection: Along with the helmet on the head, the emblem on the chest is a part of the robot that's important for creating an impression the viewer. Thus many patterns were considered for the emblem, including stylized birds and letters as well as mechanical parts, as shown in these images.

Story • The time is the future. On the planet Solo, to which humanity has just begun to emigrate, a spaceship and a huge humanoid robot are unearthed. Due to a misunderstanding over the limitless power hidden within this robot known as the Ideon, the Earth people find themselves at war with the alien Buff Clan, and they begin a desperate flight for survival as they escape to the Milky Way galaxy...

Commentary • The most unique of works, which depicts the main robot as "a tool that humans can't control" and pessimistically shows people losing their lives at the mercy of this "tool." As well as human relationships that expose their deepest egos, it was famous for its action scenes filled with epic battles and wildly dancing missiles. It aired at 6:45 PM Thursdays on the Tokyo Channel 12 Network (changing to 7:30 PM Fridays as of episode 22), starting May 8, 1980. 40 episodes total. Theatrical film versions were also released in July 1982.

Staff •

Cast •

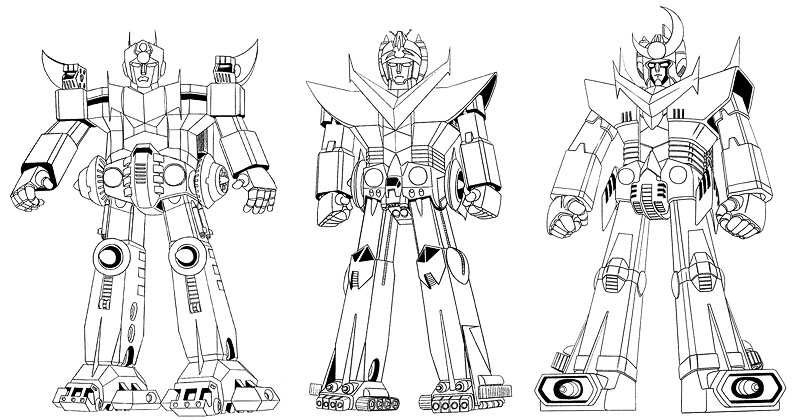

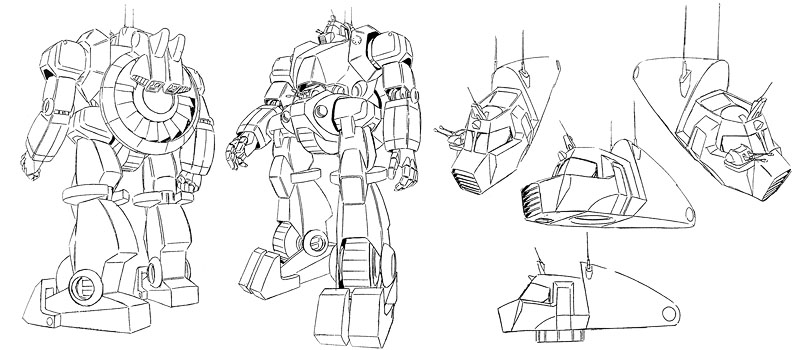

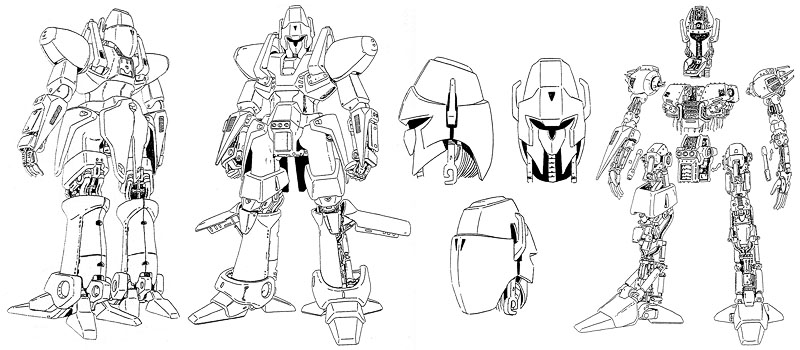

Ideon: The mecha design was by Submarine, but their work was cleaned up for the anime by animation director Tomonori Kogawa.

Head: The Ide mark on the forehead was added at Director Tomino's request.

Right: A drawing by Tomonori Kogawa. This impressive pose was depicted in the opening film as well.

Orthographic views: Orthographic views that emphasize the combination. These were made with a focus on functional aspects such as the alignment of all the parts during transformation and combination, rather than on looking cool as drawings.

Cross-section diagram: A setting illustration showing the positional relationship between the cockpits of each machine after they combine to form the Ideon. Vehicles called Moviolas allow movement between the cockpits.

This work began with a request from the toymaker Tomy to create a new robot anime. Though the completed toys themselves were complex and sophisticated, the content of the work was so philosophical that it couldn't capture the young audience that was the original target. It struggled in the audience ratings and ended up being canceled, with the originally planned one-year broadcast run cut off at three cours.

However, during the broadcast, a strange excitement began to grow among some of the fans. Thanks to the momentum of the ongoing anime boom, the canceled part of the story was finally released as a theatrical movie.

Though this work is often discused in terms of its challenging content, it was also remarkable as an action anime, and we have yet to see an anime surpassing the scale of this "chase drama with a vast galaxy as its stage."

I began designing a combining robot at the request of Mr. Eiji Yamaura, who was the head of the Sunrise planning department at the time. I think the initial concept was that a school bus, an armored car, and a tanker truck would each transform into aircraft, and then combine to form a robot.

The protruding shoulders weren't intended to make the silhouette more interesting, it's just that there was no other choice given the transformation mechanism. (laughs) That's what happened when we physically combined the three mecha, and the silhouette came after the fact.

Anyway, I had my hands full just thinking about things like the transformation structure. I honestly still regret that I couldn't give proper attention to the color scheme and relief decorations of the body itself. I've done various anime designs, but Ideon is the only one I still get interviewed about like this.

In the planning stages, this work had tentative titles such as "Space Runaway Gandorowa," "Space Combiner Ideon," and "Liner Space Ideon." The Soloship was originally given the name "Mayflower" after the 17th-century migrant ship that carried the Puritans from England to the American continent, but this was changed due to trademark issues.

As for the protagonist Yuki Cosmo, he was named "Yuki Shin" when Tomonori Kogawa drew his first rough draft. Two versions were drawn, with and without the Afro hairstyle.

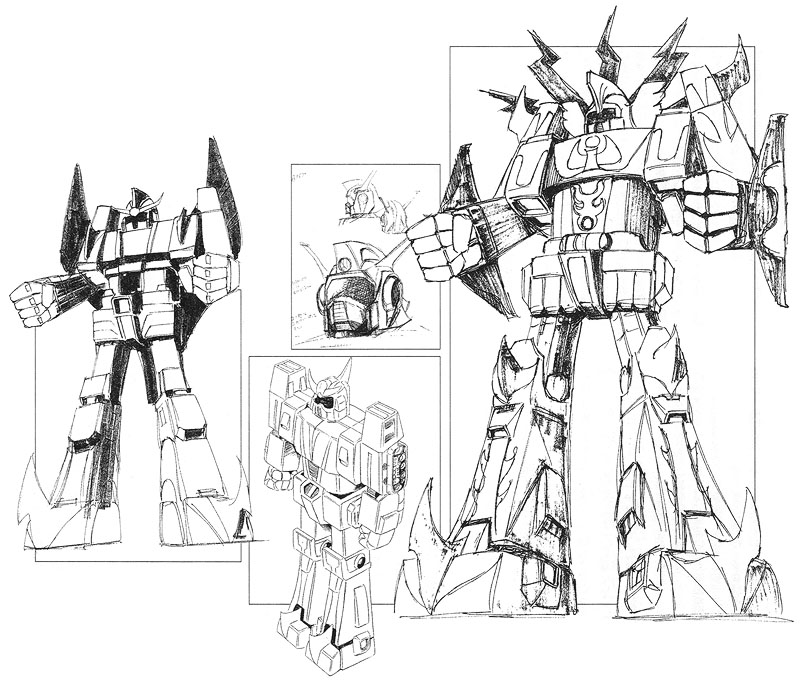

Left: It seems the idea of storing the head inside the shoulder parts was decided at a very early stage.

Center: An early head design. The expressionless goggle-type face was suggested by Director Tomino.

Right: A distinctive design with lightning-bolt decorations on its back. Its body is covered with stylized flame reliefs.

(1) Jidaigeki (時代劇) is a genre of historical drama, typically in live-action film and television, set before the Meiji restoration.

(2) The Japanese subtitle 無敵超人 (muteki chōjin) literally means "Invincible Superman."

(3) Presumably the earlier proposal was by scriptwriter Yoshitake Suzuki, who is credited with the original story.

(4) Shingo Kozuki is a supporting character, voiced by the same actor as Gundam's Kai Shiden, who starts out as a rival to the protagonist Kappei and blames the heroes for the destruction caused by the ongoing battles. One might say he's very much a trademark Tomino character type.

(5) The final subtitle 無敵鋼人 (muteki kōjin) literally means "Invincible Steel Man."

(6) In the animation, the Daitarn 3's transformed modes are called the "Dai-Fighter" and "Dai-Tank."

(7) This original sponsor was apparently the toy company Bullmark, which went bankrupt in late 1977.

(8) The Japanese term used here is 下町人情 (shitamachi ninjō), which I phrased above as "working-class humanity."

(9) Tadao Nagahama was a legendary robot show director, who took over from Yoshiyuki Tomino on Brave Raideen and went on to direct the so-called "Robot Romance" trilogy of Com-Battler V, Voltes V, and Daimos. He died unexpectedly in November 1980, at the age of 48.

(10) The actor Yujiro Ishihara became famous as a young leading man in Nikkatsu's live-action movies.

(11) Ganbare (頑張れ) is a phrase of support and encouragement.

(12) The Japanese expression 竹を割った (take wo watta), which literally means "splitting bamboo," indicates someone frank and refreshingly straightforward.

(13) The Japanese text here credits Yatate and Tomino with "original plan," but I've revised this in my English translation to match the actual TV credits.

(14) The Japanese text here credits Submarine with "mecha design cooperation," but I've revised this in my English translation to match the actual TV credits.

Success, failure, and then revival. Director Tomino says "I'd like the youngsters to know my history over the last twenty years and use it as a textbook." It's a passionate message for those who must live through the turbulent end of the 20th century, and then into the new one!

PROFILE

After serving as series director for the first time on the 1974 TV anime Triton of the Sea, he's worked mainly on Sunrise works. In particular, he became famous for 1979's epochal robot anime Mobile Suit Gundam, and he is attempting to create a new Gundam in 1999.

I didn't touch it at all. That was decided by the sponsor and Sunrise, and the title "Zambot 3" had already been decided by the time I came on board. But with the following Daitarn 3, it was after I joined, and I think it was settled by me saying something like "I think Daitarn 3 is fine."

Of course. As far as the title, I just thought it would be fine to go with something straightforward, without thinking too much about it.

I did both Zambot and Daitarn, but the credit went to the Sunrise planning office. So with Gundam, I started using the "Rin Iogi" pen name. Unless a company recognizes individual artists and individual independence, the company itself won't survive. So I used a pen name, because saying it was the Sunrise planning office created the misconception that the entire organization created it.

As for Gundam, we initially tried to go with the title "Gunboy," but when we checked the trademark we couldn't get it. So eventually we decided on "Gundam." However, "Gundam" is actually also trademarked in a field unrelated to film or publishing, so we added the subtitle "Kidō Senshi."

I started working on the novels before the TV version of Gundam itself became a hit. Mr. Haruka Takachiho was the intermediary who introduced me to Asahi Sonorama. Anyway, I started on it wondering "Could you make a novel out of a robot show?" The first volume was published by the time the show went off the air. Then it became a breakthrough hit, so I wrote a second and third volume as well. (laughs)

Basically, the novel version is close to the story I'd wanted to tell. That's why the contents diverge from the TV version. At first, the idea of turning a robot show into a novel was completely ridiculous back then.

Maybe in hindsight, but I have no idea. Ten or fifteen years later, staffers who read them came into the workplace and called me all sorts of bad names, saying "The content is different from the TV version!" (laughs) When people ask me "Why did Amuro die?" it's because otherwise I couldn't have turned it into a novel back then. Since robot anime was dismissed as not being science fiction, I was trying my best to explain the mobile suits and make them seem more science-fictional, so that it would be at least a little closer to SF. (laughs)

That's because I liked Banjo. I was wondering whether I could create another work with him, and since anime novels were now recognized as a genre, they were also easy for me to write. But I regret that I got carried away with how easy it was, and turned it into purely a commercial job. However trashy a work may be, there's value even in trashiness. (3) But there's still one absolute condition, and that's "if the creator isn't seriously fired up, they can't grab readers or viewers."

This is something I can say now it's been ten years, but I was confronted with the fact that I ultimately couldn't become an author, and I didn't have that kind of ability as a writer. I've realized that it's very wrong to keep on writing novels and making TV series out of habit. Fifteen years later, I sometimes meet people who say "Director Tomino, I've read all of your novels." My apologies to those people, but if you've witnessed Tomino's self-indulgent history, then I'd rather you used it as a textbook counterexample.

As far as I'm concerned, the mediocrity of my work from Gundam ZZ onward was because I was creating works only to suit Sunrise's convenience. That may have made me a businessman, but I continued my career for more than ten years being neither an author nor a director. For a few years after Gundam, as you can see from my works, I was trying at least a little bit. (laughs) But looking at the remaining ten years, I couldn't make anything that satisfied even myself, and with V Gundam I really finished myself off.

Going through an experience on the boundary of life and death, I realized I couldn't just lay down and die, and I began searching for work that would bring me back to life. That turned out to be Brain Powerd, which I consider my second debut after Triton of the Sea. Completely aside from its evaluation as a work, Brain Powerd has become something very precious to me.

It was an unusual logo for the time. As for the "Ideon" title, that was definitely my own suggestion. Once again, we'd had issues with trademark registration, so we ended up going with "Ideon." But to me, the meaning of something loaded with Ide expressed the story's theme very obviously. I hated it because it was too direct, and I wondered "Is Ideon really okay?" As a creator, it was pleasant to be able to do something like that with a robot show. But that said, it's not really good to make it so clear-cut.

As for the movie version, the clear reason for doing that was the desire to let Japan's current filmmakers know that even robot shows could convey a story. With that work, I wanted to raise my hand and show the Japanese film industry that I was actually doing things like this even though I was only making animated robot shows. That's why I had to make it so clear-cut, and because I did it so seriously, I was able to see it on the big screen. But even after Ideon, the Japanese film people made a point of haughtily saying that it was a pity that people wouldn't let Tomino make a proper movie.

And that's what led to Evangelion and Princess Mononoke. You won't think it's arrogant of me to say that, will you? (laughs) Audiences only watch things that interest them. Mononoke was number one at the box office, but it's terrible that was just the fashion of that year.

I gave "Xabungle" the OK, but I think it was one of several title proposals that already existed. The only thing I played around with was spelling it with an initial "X" rather than a "Z." That was partly to differentiate it, but when I made the rough storyline, I wanted to include letters that were as rough and angular as possible. The letter X hs a lot of sharp angles, right? (laughs)

It's completely the opposite. (laughs) It may look that way at first glance, but to me, it's purely about the mecha. The mecha was all I was thinking about, and though I was really upset the plastic models didn't sell, I love the walker machines so much that they're the only plastic models I'd ever want to build!! (laughs) Tools should be things like that, and they suit me best because that's what tanks would be like if you made them humanoid. So I still believe there's no reason for modelers to dislike walker machines, and I wish there were larger-scale plastic models of them, like 40cm or so. (laughs)

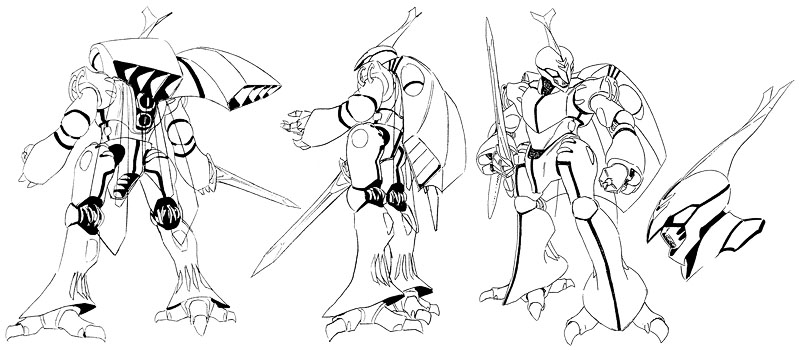

When it comes to the main mecha, Dunbine was only time I was able to clearly incorporate my interests as an original creator. It felt suffocating to keep doing the same kinds of mecha shows, so I wanted to take a different approach. Thus I came up with the setting for the Aura Battler concept, and Dunbine was my attempt to see if I could turn it into an actual work.

At the time of Dunbine, I was thinking that mechanical-looking tools basically weren't what humans needed. I wanted to try creating setting for tools that were closer to the body.

I was thinking purely of something close to humans, something ecological. But since the aura battlers had to have shells, I decided on insects rather than reptiles or mammals. That was my reasoning.

It's also important, though I wasn't able to include this in Dunbine, that animals' bodies are very well made. The shell itself is like a magic mirror. It has the feature that you can't see into it from outside, but but you can see out from within it. Even if you remove a bone from the human body, it'll be replaced within a one-year span. But it's because organic things aren't eternal that we've been given skeletons we can use for a hundred years.

If you measure their strength numerically, mineral things are quite functional in the moment, but when you consider durability and versatility, I thought they might actually be close to something biological. That's why I wanted to try biological things in the form of aura battlers.

"Dunbine" went through just as I wanted. The only thing was that the title I'd originally established was "Amalgan." Then the sponsor responded "Come on, you must be kidding." But there was a clear reason for that. They said "Don't do that, because it'll sound like we have a bunch of leftover toys." (4) (laughs) Since I liked the sound of it, I introduced a character called Amalgan in my novels so the name wouldn't be forgotten.

With the Billbine, they'd asked us to introduce a new aura battler. There's no meaning to it because it's just a step in the process, but it became "Billbine" because we had to build the next one.

Eh? Hm, I don't remember... I guess we gave it the working title "Sirbine" because "Amalgan" had been rejected. As for why it became "Dunbine," that's probably because it had two "n" characters. At the time, there was an iron rule that anything without an "n" in the title for good luck would be jinxed to fail. (5) (laughs)

Right, and that's why it ended up like that!! (laughs) With recent works, it seems the creators can give them any title they please, but back then we were very superstitious. At the time of L-Gaim, I ended up going with that title because I was tired of that. But it was just self-indulgence on the part of the creator, which is something that actually pervades the entire work.

Writing "Jūsenki" and reading it as "Heavy Metal" was just meant to reflect the mood of the times. You could read it as either "Jūsenki" or "Heavy Metal," but unfortunately neither of them included a single "n." When you see that kind of selfishness from a creator, something like Blue Gale Xabungle works better even ten years later. With that in mind, I feel I shouldn't be so selfish about the naming.

That's why I still think of L-Gaim as a fatal injury, and that's the background behind my becoming focused exclusively on Gundam works like Z Gundam and Gundam ZZ. Even within Sunrise, after Xabungle they felt that if they let Tomino do something, then they had to limit the parts where I could do as I pleased. So I was caught in a situation where they wouldn't let me work on anything but Gundam.

To tell the truth, we often talk about failure only in terms of the point when we actually fail, but I think the fundamental cause of that failure lies within the high point. My production chronology clearly shows the progression of successes and failures, followed by "maybe I'm dead as a creator," so I'd be grateful if young people could read something like that from my history. It's not just my own personal problem, but a trap that many people fall into.

What I mean is that, when you have a hit or things are on the upswing, you should try to use your senses and intelligence to be careful about what you're doing. If you do that, I think you can find a methodology that will slow your decline and let you carry on peacefully until you die. That's something I want both creators and middle- and high-school students to understand.

Not at all. But Mr. Okawara has been turning robots into characters in the anime genre for more than twenty years, so his powers as a concept worker shouldn't be taken lightly. Instead, what I want young people to understand is that, whether Okawara designs are truly good or bad as designs, there's still a problem. The problem is that he's been doing it for 25 years, so when young people look at them, there are parts that seem dated and uncool.

Of course, Mr. Okawara is aware of this as well, and I've given him the order "Can't we incorporate a little more of the feelings of young people?" He did as I asked, but he's still just one person doing it on his own, and of course that's not so easy to incorporate. That's Mr. Okawara's struggle, and I know it too. Ultimately, when I look at this span of 25 years and wonder whether a designer has appeared who should replace Mr. Okawara, I'm confronted with the fact that they haven't, so someone like me has no basis for evaluation.

Even when younger people refine the lines and make the individual parts look cooler, I don't think anyone has ever stolen the essence and structure of Mr. Okawara's characterization-friendly designs. Mr. Okawara has an instinctive ability to turn mecha into characters. Words and concepts have to be expressed in the pictures, so if there are designers who don't want us to just leave it all to Okawara—and I think there must be some out there—then I'd like to say, go ahead and try it. It's frustrating, but that's why Okawara design is so great.

Well said, that's exactly it. In Europe, people who want to become artists first enroll in schools of architecture. When I learned that about ten years ago, I thought that made sense. If you come at it via architecture, you're studying the construction of past buildings as a designer. But that's not the case in Japan, and I don't think people who like mecha can surpass Okawara designs by becoming mecha designers right away.

To say a little more about Mr. Okawara, he never studied architecture, and his innate talent is something he naturally had from the beginning. But the thing is that Mr. Okawara began his professional career as an apparel designer. The point is that apparel is about looking at the human figure and seeing it as a character. He combined that with the architectural design sense he already possessed, so he wasn't starting purely from imagination.

I think that's what design initially requires. So to everyone who wants to design mecha, if you're only doing mecha design, please stop that immediately.

That foundation is actually realism, not fiction. This time, I've asked Mr. Syd Mead to do the design for Turn A Gundam, but he originally studied as an industrial designer, and also did design work for tangible things like automobiles before eventually entering the SF world.

Design that requires maturity from the designer isn't based simply on good taste. That taste, I can assure you, isn't something you can cultivate through designs that are just a pack of lies.

They do have that ability in common. They instinctively understand space and the solid structures from which objects are formed. When I finally returned to the workplace with Brain Powerd and Turn A Gundam, I realized that people who aspire to become anime mecha designers don't know the basic principles and lack any academic fundamentals. So to those who are currently studying in college to become architects and or industrial designers, I'd like you to stick with it. Go out into the field, draw up some blueprints, and then join us in this world.

This time, we'll be able to see Mr. Syd Mead's work up close, and perhaps the difference in our cultural spheres will make us wonder "What are the areas where we're most lacking?" I want everyone to see that aspect as well.

When I watched the video of the Honda P2 in motion, I thought I'd seen a glimpse of hell. It's a tool that humans should never have, so I completely reject it.

Not at all! It's because the only reason I can see for developing something like that, which has no value to humanity as a convenient tool, is sheer arrogance. And that statement isn't just my own personal physiological reaction.

For example, nuclear warheads have been reduced one by one since the end of the Cold War. But just because there hasn't yet been a nuclear warhead stolen somewhere, that's no reason to blindly accept that everything is fine and the warheads are safe. Even if we place tools out of our reach, nobody thinks about what might happen if they get out of control. Or rather, the more we know about it, the more we hit the brakes and say "I don't want to think about it."

I know there's a need for medical and nursing robots, but there's no guarantee they won't get out of control and kill their patients. In short, the guardrails don't work. A certain military commentator gave me a great example, saying "Is anyone out there using a mobile phone properly?" (laughs)

That's why I treat robots only as vehicles, or only as tools. Mobile suits are also positioned as tools and weapons, but it feels like Gundam is still stuck in robot-show territory. That's why I really don't want to call it a robot show.

When I was a boy, I loved rockets and aircraft, so I can't say I hate mecha. I turned to the arts and humanities along the way, but I do like mecha and machines, and mechanical elements are reflected throughout film and photography, from the visual aspects to everything else. That's why I like movies, and so I had no objection to going into anime, which has to be made even more mechanically than live action using entirely artificial materials.

I've also learned that you can't make films without cultural literacy. Films are about storytelling, and you can't make them based only on mechanical technology. What I've come to realize, after doing so much work on things like sports and gag shows, is that a story can never be built purely on mechanical sensibilities. You may be able to line up beautiful CG movies just because visual technology has advanced, but whether or not those count as film is a different question.

What I'd like everyone to understand is that film is something made from a well-balanced mix of mechanical hardness and narrative softness, so you won't be able to make it just out of love for mecha, or just out of love for story. Likewise, as for whether you can make anime just because you love it, I can easily confirm that's not the case.

Right now, it's not just a matter of anime or film or whatever, but I feel the perceptions and epistemology of all Japanese people are collapsing. (6) The time has come to reconfirm the epistemology of anime as well. So I practiced for this with Brain Powerd, and Turn A Gundam will continue and complete it. This time, I'll be using the Gundam name. I'm making a work with the idea that we shouldn't just create things, but that we need to go back to the starting point so that we can improve our epistemology.

I long ago discarded the idea of it being part of the 20th anniversary or whatever. (laughs) In the present day, Earth functions like a single nation, but since that's such a radical development, there's no way it won't end in collapse. You could say the modern era has come to Tobaguchi. (7) I believe this collapse will be a thorough one, and once we get there, things will only go downhill. We're getting to the point where if that doesn't happen, Earth itself won't survive.

When I thought about that, I didn't know how humanity might reach its next zenith. Since I don't know that, I'm trying to do it in fiction with Turn A Gundam, and I want this work to show that there might be another way of looking at it. Perhaps we're now in an era where we must once again refine the society that our generation has created based on misunderstandings.

Thinking about it like that, I realized it would be better to do this job thinking of Turn A Gundam as a completely new work, rather than an extension of the previous Gundam. Maybe it's only anime, maybe it's merely the genre they call the robot show, but it has to be our job to break away from those aspects a little. I believe this is our mission as creators as we enter the 21st century.

(1) The Japanese term the interviewer uses here, 大胆不敵 (daitan futeki), means "fearlessness," "daring," or "a daredevil attitude."

(2) Tomino wrote four novels in this series. Originally serialized in Asahi Sonorama's magazine "Shishi-Oh" (Lion King), these were published as collected volumes between 1987 and 1992.

(3) The Japanese term 低俗 (teizoku) literally means something like "vulgar" or "lowbrow."

(4) Tomino's preferred title, "Amalgan," sounds similar to "amaru" (余る), a verb meaning that something is surplus or left over.

(5) The Japanese word "un" (運), meaning "luck" or "good fortune," sounds similar to the "n" character. It's possible that this superstition was specific to Tomino works, because it doesn't seem to have been followed in many other Sunrise works of the era.

(6) Epistemology—認識論 (ninshikron) in Japanese—is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature and sources of knowledge.

(7) Presumably a historical reference of some kind. Tobaguchi (鳥羽口) was one of the seven portals of Kyoto after the city was reconstructed by the warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi with defensive earthwork walls.

Before the final draft is completed, many rough designs are drawn up for consideration. Here, we will introduce some carefully selected gems from the early designs for the main characters featured in various Sunrise works.

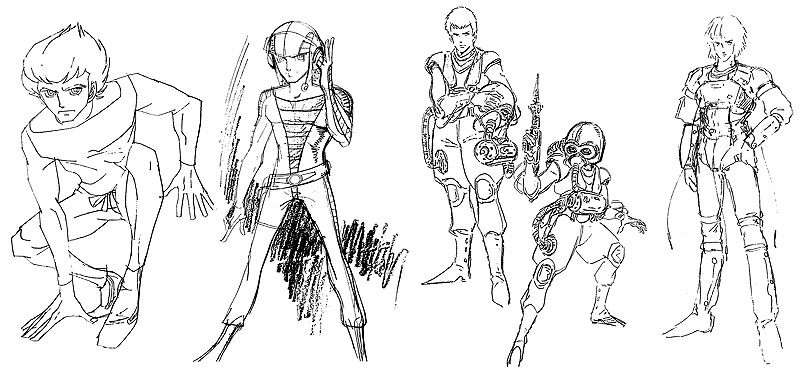

Super Machine Zambot 3: The three protagonists as drawn by Ryoji Fujiwara, who was also responsible for mecha design. Though the formation of two male and one female character is the same as the final draft, their visuals are completely different. Is the boy on the right side main character-class?

In their battle costumes, the designs are reminiscent of medieval European armor. Though the boys and the girl use identical designs, their helmet marks are all different.

The Unchallengeable Daitarn 3: An early design for the protagonist Banjo Haran, drawn by Hitokazu Kokuni (a pen name for Tomonori Kogawa). This design drawing was then cleaned up by character designer Norio Shioyama.

In terms of design, Banjo's battle costume is essentially unchanged in the final draft. From the start of planning, the aim was "a robot anime version of 007," so the protagonist was established as a young man.

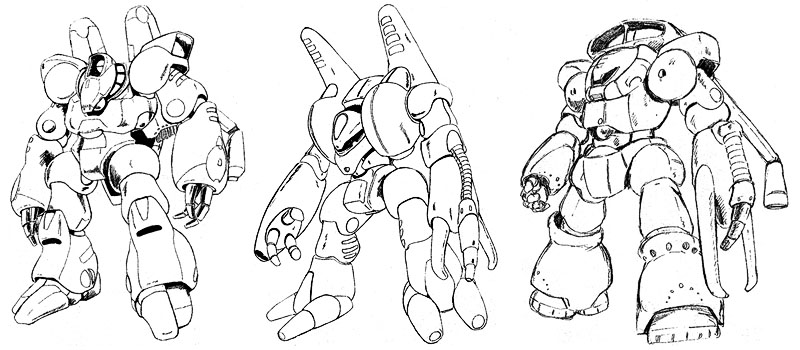

Armored Trooper Votoms: Design drawings of the protagonist Chirico Cuvie by character designer Norio Shioyama. The chest tank connected to his helmet is striking, and the tubes on his arms were meant to be plugged in while inside the robot.

Heavy Metal L-Gaim: A design drawing of the protagonist Daba Myroad. It was drawn by Mamoru Nagano in August 1982, at which point the title was "Mugen Star." The belts wrapped around his arms and knees are supposed to be anti-G bands to prevent backflow of blood.

Translator's Note: As above, I've focused here on translating the parts that provide critical analysis or behind-the-scenes production info.

Story • Following the traditions of his royal family, Prince Edward Mito, heir to the planetary kingdom of Edon which rules many other nations, goes out in disguise to inspect each of its planets. But evildoers run rampant on every planet, like local lords who exploit their power to persecute the weak, and money-hungry space merchants! Together with his loyal retainers Duke Skede and Baron Karks, Prince Mito uses the giant combining robot Daioja which has been passed down through his family to eradicate these evildoers.

Commentary • A work of light entertainment which incorporates the flavor of the well-known historical drama Mito Kōmon into a robot anime. The image of the protagonist as a compassionate person who loves justice, and the heartwarming story development in which good is rewarded and evil punished, made this a robot anime which could be safely watched by the entire family. With Katsutoshi Sasaki continuing on as director from Trider G7, it started on January 31, 1981, airing at 5:30 PM Saturdays on the Nagoya Broadcasting Network. 50 episodes total.

Staff •

Cast •

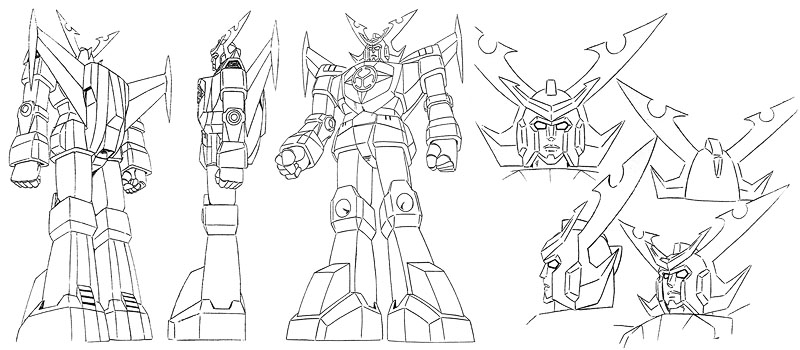

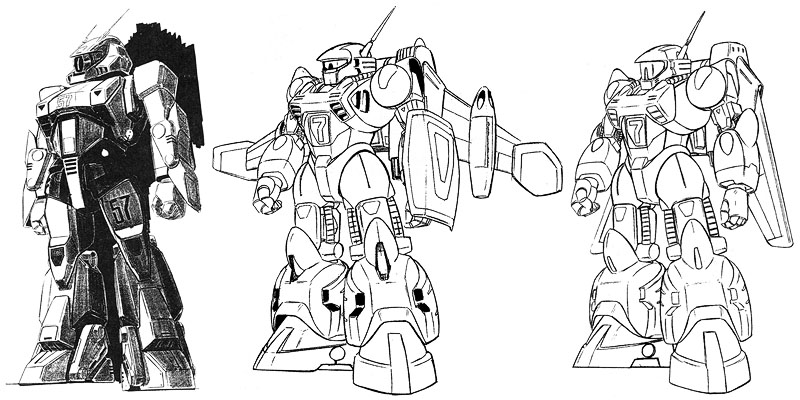

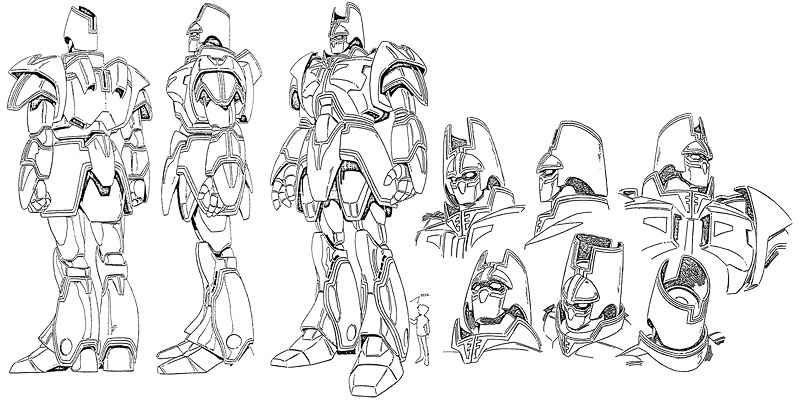

Daioja: A Sunrise "robot with a mouth" in the tradition of Daitarn and Trider. The silhouette of its overall body is also a direct descendant of those two.

Head: As well as incorporating a decoration inspired by Japanese helmets, the head also reflects the three-leafed family crest of the Tokugawa family. This is a good example of how well the robot's design matches the world of the story.

Clover continued on as a sponsor from the previous program. Toys were released that combined just as they did on TV, but their forms prior to combination were problematic, and the so-called standard types without combination gimmicks ended up selling better than the deluxe types.

At the proposal stage, the names of the robots before they combined were "Prince Ace," "Suke Robo," and "Kaku Robo." The characters were named "Prince Mito," "Suke Duke," and "Kaku Baron" respectively. In the actual show these were slightly different, but the image of "old Prince Mito" and "Suke-san and Kaku-san" was already in place at this stage.

I created the name "Daioja" from the idea that, after touring various nations, the prince will eventually become a great monarch. (1) As for "Mightiest Robo," I'd actually been thinking about that since the time of "Zambot 3," and it was someting I'd set aside for when I couldn't come up with an interesting subtitle. (laughs) (2)

Though real robots had become the mainstream at that time, the previous Trider G7 had been well-received, so we decided to once again go with an approach aimed at children. Having three robots combine into a single giant one worked well in the anime, but it seems it was hard to reproduce that in a toy with the technology of the time, so unfortunately it was somewhat imperfect as a product.

All I was given by Sunrise was the coded description "the A robo, B robo, and C robo combine to form the D robo." (laughs) It felt like I was free to do as I pleased from there... So it was fun fitting them together like puzzle pieces.

I believe I'd heard ahead of time that Daioja would be a story like Mito Kōmon, and that the robot would be a substitute for the seal case. (3) That's why I put a three-leafed crest on its chest. I gave the horns on the head a three-leafed motif as well. Since Mito Kōmon was the template, the robot itself was designed with a more Japanese image as well.

Because TV anime frequently uses recycled stock footage and horizontally flipped film, the mechanics are often designed to be bilaterally symmetrical, so as not to create problems on these occasions. Likewise, Daioja used a combination concept of "stacking from below" to make sure the robot was symmetrical.

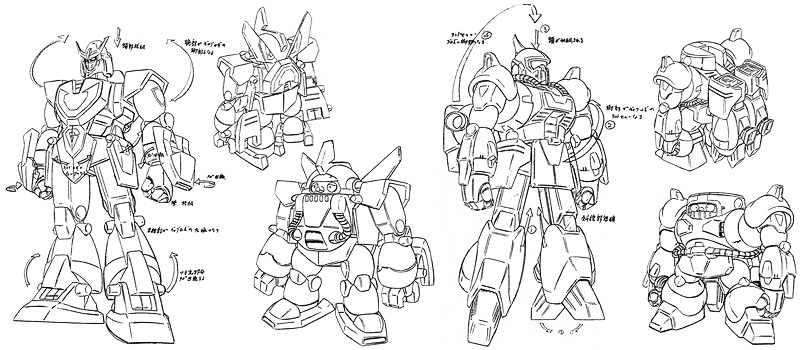

Since the plan was based on the idea of a robot anime version of Mito Kōmon, these two versions of the main robot from the planning stage already have a three-leafed crest mark on their chests. At the planning stage, the three combining robots were designed as a samurai type, a gunslinger type, and a Roman warrior type. Thus each would have distinctive performance and visuals.

Story • In the year S.C.152, a war of independence breaks out on the planet Deloyer, a colony of Earth. Crinn Cashim, the son of the Earth Federation Council chairman, has doubts about his father's policies. Joining up with the guerilla group "Fang of the Sun," he becomes the pilot of the Dougram. For Crinn, this is also a fight for independence from his father...

Commentary • The first in a real robot series directed by Ryosuke Takahashi, this ambitious work depicts people caught up in the currents of history during Deloyer's war of independence. With the weapon-like aspects of the combat armors highlighted even more than in Mobile Suit Gundam, and the drama placing an emphasis on the world of politics, it incorporated viewpoints never seen in traditional anime. Because the first episode was designed to explain the basic setting of the complex story to the viewer, it also had strong elements of a pilot film. It aired at 6:00 PM Fridays on the TV Tokyo Network (changing to 5:55 PM as of episode 20), running from October 23, 1981, to March 25, 1983. 75 episodes total.

Staff •

Cast •

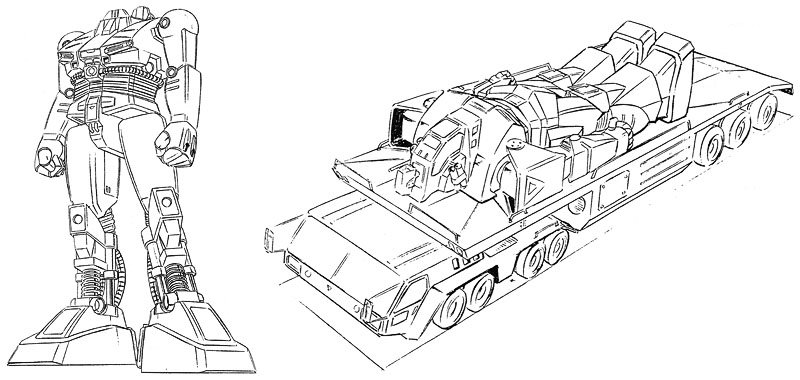

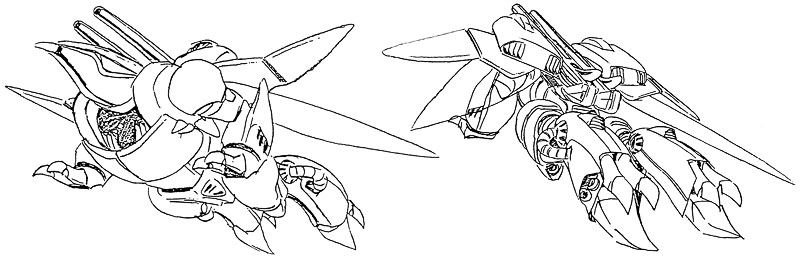

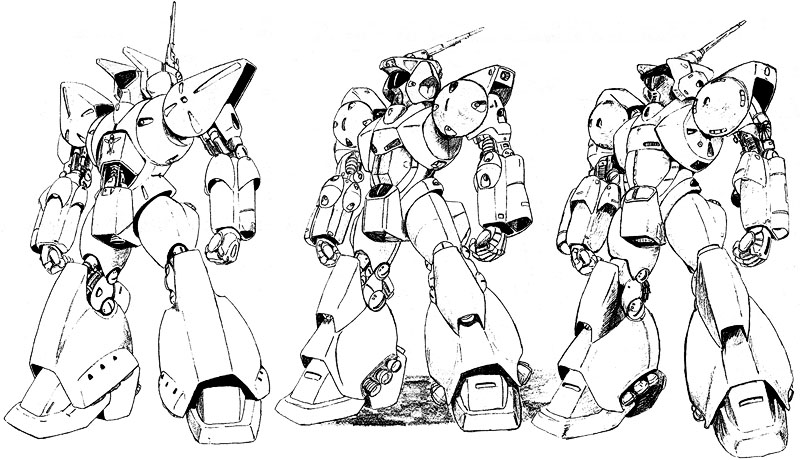

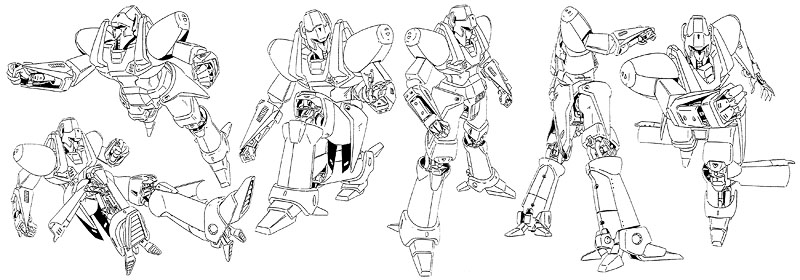

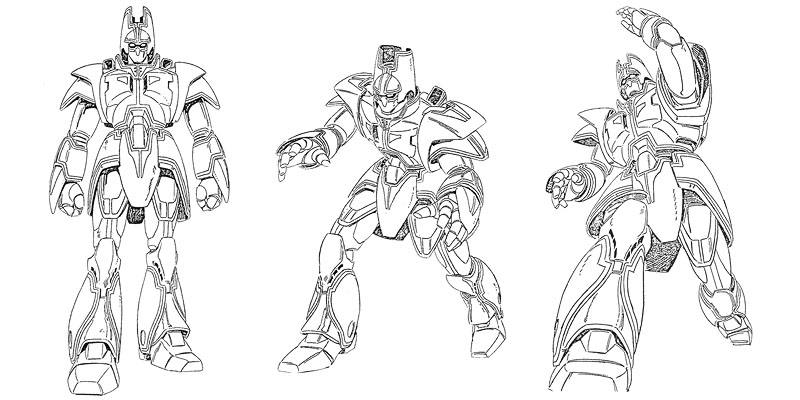

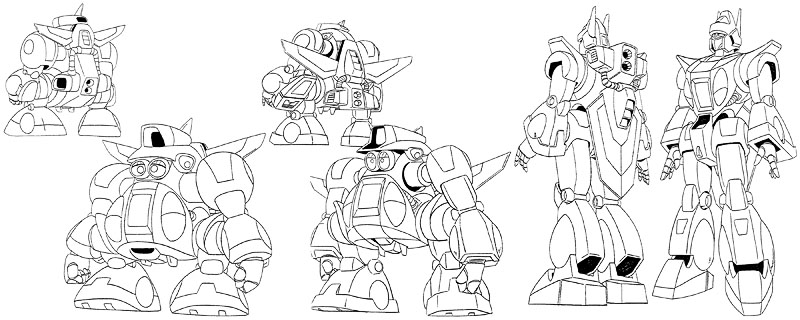

Dougram: The design has a heavyweight feeling very typical of Kunio Okawara. The head's lack of facial features makes the Dougram seem more like a weapon.

Head: The cockpit design actually originated from construction machines such as bulldozers, in which the operator's location is visible. It took on its current form by adding the flavor of things like combat helicopters.

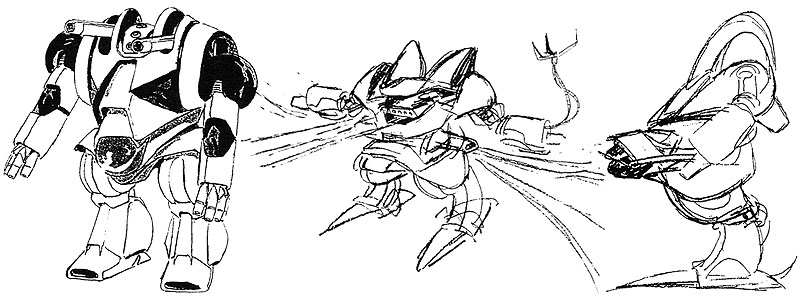

Pose collection: Perhaps because it was designed to prioritize its image as a weapon, no common "hero robot" poses such as punching, kicking, and jumping were drawn. The design extended even to the soles of the feet, which were seldom seen onscreen. There had never been a robot with such detailed setting, which shows how it was striving for realism.

Character comparison: The Dougram's overall height of less than 10 meters made it about six times human size. This was because excessively huge robots were unrealistic as weapons operated by lone individuals. See our interview with director Ryosuke Takahashi for further details.

Internal drawing for cutaway model: This internal cutaway setting was created for use in the toys, and it differs from the setting of the Dougram's interior in the anime itself. In particular, the spring-like details in the ankles were included specifically for the toys. As well as plastic models, the three-dimensional Dougram toy releases included Dual Models made from hybrid plastic and die-cast metal materials, and 1/144 scale die-cast models.

Federation Forces trailer: The Dougram was loaded onto a large trailer for long-distance movement. The members of the "Fang of the Sun" guerilla group also moved between battlefields by riding on this trailer. The song the "Fang of the Sun" members sing in the show, "West, East, North and South," is a parody of an insert song from the classic Japanese movie Westward Desperado.

In terms of mecha setting as well as drama, this work could be called another step forward for the real robot approach that blossomed in Gundam. The main robot was portrayed purely as a tool rather than as a hero, and viewers were particularly shocked by the first "faceless robot" in anime history.

The main sponsor was Takara, returning to robot anime for the first time in a few years, and since the plastic models and other toys sold well, it was decided that the broadcast run would be extended. In the end, it became exceptionally long-running work with a total of 75 episodes. In July 1983, a theatrical version called Document Fang of the Sun Dougram was also released, in which the TV version was re-edited to look like a newsreel.

Up until the Dougram, the main mecha of a Sunrise robot anime always included some kind of combination or transformation gimmick. This could be considered inevitable for the robot anime of the time, which coexisted in a relationship with the toys, but from the middle stages of planning the setting concept for the Dougram was "a robot that doesn't combine or transform."

The production side took this "non-transforming approach" because, after the success of Gundam, they felt a robot anime aimed at older audiences might be possible. In other words, they were trying to make "mechanical believability" the main appeal of both the toys and the work itself, rather than flashy transformations and combinations.

On Dougram, by the time of my first meeting with Takara, they'd already come up with the idea of a toy where "it has an internal structure, and armor parts are attached to it." The concept was to eliminate the transformation and combination that were common in robot shows, and Takara's idea was that we could achieve play value for the toy by reproducing the internal mechanisms in a Dual Model. I think we felt that if we used transformation and combination instead, it would seem childish and wouldn't create the authentic military feeling we were aiming for.

As for the faceless design, I wanted to try creating something new. The sponsors okayed it, and I don't think Sunrise had any particular requests for the mecha design. Come to think of it, a little while after Dougram, I half-jokingly drew a Gundam with a cockpit for its face as well. (laughs)

When the planning of Dougram started, it had tentative titles like "Space Buffalo" and "Zactics." The final title "Dougram" is supposed to include the nuance of the word "Zigzag," with the image of guerillas who move between battlefields as they fight. (5)

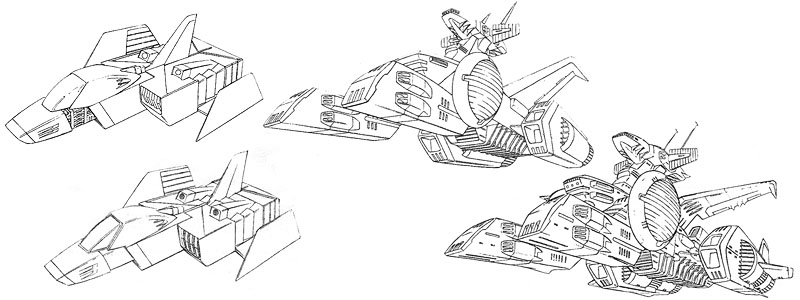

At a very early stage of planning, consideration was also given to robots based on traditional toy-like concepts such as "a small transforming machine combines with the robot to form the head" or "the main robot combines with a transforming transport craft." However, as the plan itself progressed with a clear emphasis on "military flavor" and "a realistic approach," these kinds of toy-like ideas naturally disappeared.

Right: This early design idea for a Federation Forces combat armor creates a futuristic impression compared to the blocky Dougram. From the antennas on its head, it looks like it could function even without a pilot.

Story • A story set on Earth, now known as the planet Zora. When Jiron Amos tries to steal the new walker machine Xabungle to avenge his family, he meets a girl named Rag of the Sandrats, and Elchi, the captain of the giant landship Iron Gear. Jiron joins them on a trading journey, and they eventually find themselves confronting the mysterious entity Innocent which controls Zora.

Commentary • A unique robot anime with a strong Western-movie flavor. Unlike previous real robot shows, the screen is filled with the antics of characters bursting with vitality. As the series continued, the lightness of the first half disappeared, and the second half developed into something fairly heavy with a theme of humanity's revival. Due to things like the replacement of the main mecha, fans spoke of this work as "the pattern-breaking Xabungle." It aired at 5:00 PM Saturdays on the Nagoya Broadcasting Network, running from February 6, 1982, to January 29, 1983. 50 episodes total.

Staff •

Cast •

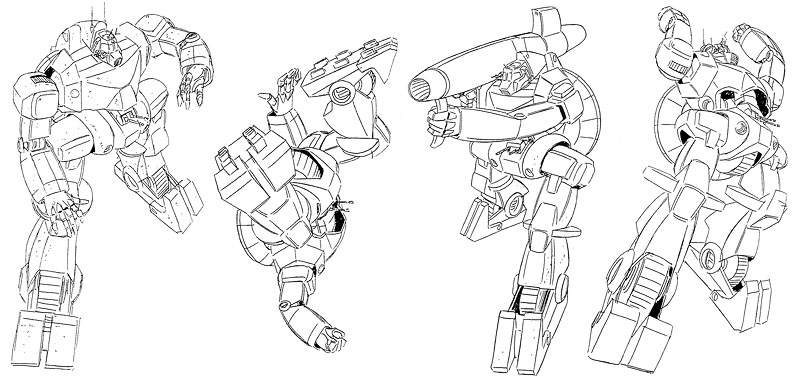

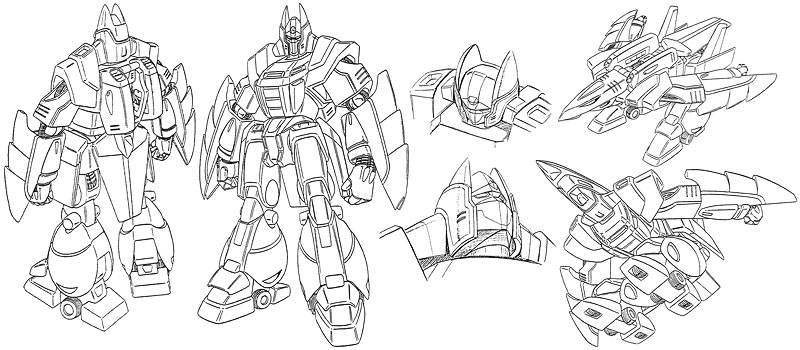

Xabungle: A relatively large model of walker machine. The fact that its cockpit is completely covered by armor shows that, unlike other walker machines, it is specialized for combat.

Pose collection: Because the designs for Xabungle were based on a concept similar to traditional hero robots, it seems this pose collection was meant to look cool and heroic. However, these typical super robot poses were all but irrelevant to the pattern-breaking program Xabungle.

Xabungle combination system: According to Director Tomino, the Xabungle's combination and transformation pattern was far removed from the approach he intended to take with this work. Perhaps for this reason, there were few scenes in the TV series which depicted the Xabungle combining or transforming.

Not just with Xabungle, but with all Sunrise robot anime at the time, the usual format was that after the concept of the robot had been fixed by the planning office, the individual director who'd been placed in charge would then create their own worldview and story. Thus, even before Director Tomino was involved, it had already been decided that Xabungle would be a work which starred combining and transforming mecha.

However, because the design and the combining mechanism of the main mecha Xabungle lacked novelty, setting was created for the giant robot Iron Gear as well. The Walker Galliar was introduced in the second half due to the wishes of Director Tomino, who felt the Xabungle didn't match the work's worldview, and the sponsoring toymaker Clover's request that a second robot show up.

The Walker Galliar, which was introduced in episode 26, was the first "new main robot" in the history of robot anime. Having a second robot now feels like a standard convention, but at the time the idea of a second robot didn't exist even in tokusatsu programs, and it was a truly novel concept.

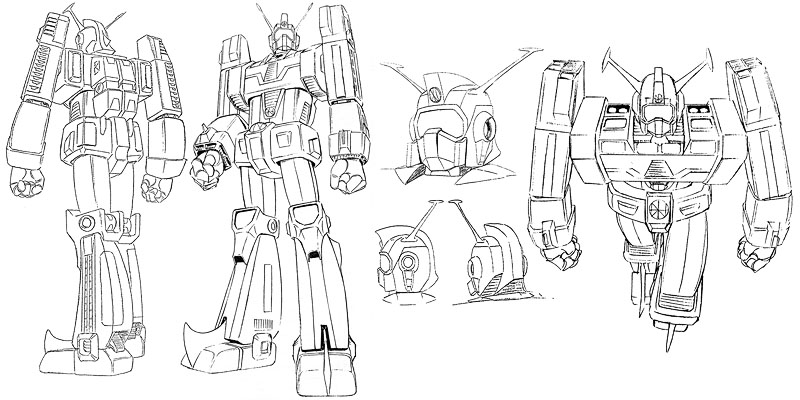

The Walker Galliar was designed by Tomonori Kogawa, the character designer, and the final draft had already been competed by April 1982, two months after the start of broadcast. After this work, replacing the main mecha would become part of the pattern of Sunrise robot anime.

The design of the Walker Galliar was based on a truck that actually existed about 30 or 40 years ago. (6) Its characteristics can be seen especially clearly in the fact that the lower body, the Galli Wheel, is a three-wheeler type. It's hard to call this a stylish design, but given the stage setting smeared with dirt and dust, it really feels like a walker machine and is well-matched to the image of the work itself. In addition to Clover's toys, Bandai also released this as part of its High Complete Model series.

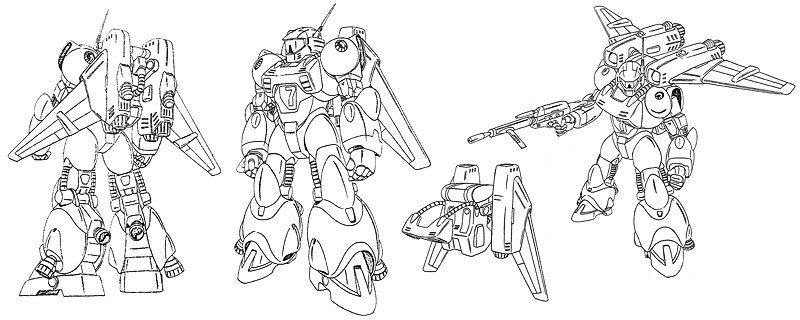

Walker Galliar: Director Tomino's request for the mecha design was "something with an interesting silhouette." This desire is reflected in the Walker Galliar's design.

Pose collection: Unlike the Xabungle, which was designed with limited moving parts because of the emphasis on its combining and transforming features, the Walker Galliar is designed on the assumption that all its joints should move.

As far as the transforming and combining gimmicks of the main mecha, I didn't have any particular requests from the sponsor Clover. We proceeded with them either okaying or rejecting whatever I'd created. Clover wasn't involved in the details of the plan itself, either, and I think Sunrise took the lead on that.

The Iron Gear, one of the main mecha, was a very big robot. But I wasn't really conscious of exactly how many meters it was. After all, when you're making comparisons to robots, that's determined by the size of things like boarding hatches. If it's something with windows, then it's decided based on the size of the windows. So if there are no points of comparison, it's all pretty vague, and it doesn't really matter whether it's ten meters or twenty.